Prologue

3rd London Territorial General Hospital October 22, 1917

Paul turned his head on the pillow and watched as Evelyn Morrow, clutching her purse to her chest like a shield, followed the nurse past the rows of beds. Her gaze did not move from the woman’s starched back as if she was unable to bring herself to look around her at the carnage the war had wrought.

The breath caught in the back of his throat and a coward’s voice in his mind whispered: Not here, not now.

He knew she had been watching and waiting for him to return to the world. Through the haze of drugs and delirium, he had been aware of her standing sentinel by his bed, clad in black from head to foot, a shadow. He knew he had to face her, but he lacked the strength to match her grief against his.

Feigning sleep, he shut his eyes.

‘Now, only a few minutes, Lady Morrow. He is still very weak,’ the nurse said. ‘I will be at my desk if you require anything.’

Paul heard the efficient clack of the nurse’s heels on the linoleum floor as she returned to her place at the end of the ward.

Through the pervading scent of carbolic, he could smell his aunt’s perfume and once again he stood on the platform at Waterloo station, a small boy clutching a battered suitcase. A beautiful woman in a blue gown had bent down and taken his hand, enveloping him in a cloud of lavender.

She hadn’t kissed him then and she didn’t kiss him now. Lady Evelyn Morrow just stood at the foot of his bed, looking down at him.

‘Paul? Can you hear me?’ Her tone commanded obedience and his eyes flickered open, meeting hers, dark pools behind the black netting that covered her face.

Evelyn clutched the metal bar at the end of the bed and the feather on her hat began to quiver as her whole body shook with the force of her emotion. ‘You promised.’ Her voice rose on a crescendo of despair. ‘You promised you would keep him safe. Where is he? Where’s my son? Where’s Charlie?’

Paul felt her grief as a palpable force, sending shock waves down the rows of beds that lined the ward. He wanted to say, ‘I promised. I know I promised but I couldn’t keep it. Charlie is gone.’

His fingers tightened on the starched sheet and his breath came in short, sharp gasps as the words formed and then stuck fast.

The chair at the nurse’s station scraped on the floor and her hurried footsteps beat a rapid tattoo on the linoleum floor.

‘Lady Morrow. Really, I must protest. Come away with me this instant.’

The nurse placed a firm arm around Evelyn’s shoulder, leading her away. Evelyn shook off the encircling arm and turned back to look at him, the tears Paul knew she had probably not allowed herself to shed were now spilling down her face.

‘Lady Morrow, please. You are overwrought. I’ll fetch you a nice cup of tea.’ The nurse’s tone softened and with her arm around Evelyn’s shoulders, she led the woman into the glassed-in office at the end of the ward.

Paul turned his head on the hard, lumpy pillow, feeling the starched linen crackle beneath his cheek. In the bed next to him, a young subaltern who had lost both his legs lay immobilised by the stiff sheets and blankets. The impeccable bedclothes, pulled up to his chin, hid the reality of his horrific injuries from his visitors, reducing the war to something neat, tidy, and manageable.

In the office, beyond the line of beds, the nurse handed a cup to Evelyn. The door opened and the Matron of the hospital entered the little office and began to berate the errant visitor for her unseemly behaviour. Lady Evelyn Morrow sat hunched in a chair like a schoolgirl and even through the glass snatches of the scolding—inappropriate behaviour and upsetting the patients—filtered out into the ward.

The nurse returned to Paul’s bedside, making a pretence of straightening his pillow.

‘Really,’ she tutted as she fussed over him. ‘I would have expected better from a lady.’

‘Outward displays of grief should be reserved for the lower classes?’ he murmured.

‘Pardon?’ the nurse replied.

‘Tell her I want to see her,’ Paul said.

The nurse straightened. ‘Are you sure?’

He nodded and with a sniff, the nurse bustled back to the office. She whispered in Matron’s ear and the older woman stiffened, casting a quick glance in Paul’s direction. Evelyn looked up as the Matron spoke. She too glanced through the window toward him and rose to her feet, tucking her handkerchief back into her purse.

Her back straight, Evelyn looked the Matron squarely in the eye and her words, audible through the glass, echoed down the long ward. ‘I assure you, there will be no repeat.’

Once more the nurse, this time in the company of Matron, conducted Evelyn to his bedside. A rustle of anticipation rippled through the ward and Paul imagined the faces of the other patients turned expectantly toward his aunt. If nothing else, her outburst had provided an entertaining highlight in an otherwise dull day.

‘Now, Lady Morrow,’ the Matron said as Evelyn took the seat beside Paul’s bed. ‘I am sure I don’t need to remind you, Major Morrow is easily tired. A few minutes, that’s all.’

Paul looked up at the ceiling while his mind framed the words. He knew what had to be said and that the words would not bring her the comfort she sought.

‘Evelyn?’

She raised her eyes and once more they looked at each other, these two strangers, bound together by ties they could not sever.

‘Evelyn...I’m sorry...’ he said, shocked at how weak his voice sounded.

She leaned toward him. ‘No,’ she said in a low voice. ‘I was unfair on you, Paul. It is I who should apologise.’

‘I know what you want to ask me,’ he said.

Evelyn did not hesitate. ‘Is he dead?’

Paul closed his eyes as he struggled with the simple word that would give her the answer she sought. He had no tears of his own to shed for Charlie. Three and a half years in the trenches had robbed him of the ability to show sorrow and his own grief for his cousin ran too deep for such an outward display.

He heard her breath catch and knew she had read the answer in his face even as he answered. ‘Yes.’

Her lips tightened in a supreme effort to control herself. ‘What happened, Paul? Please tell me how he died and why I cannot bury my son.’

He turned his face away from her. ‘I don’t know, Evelyn. God help me, I don’t remember. I just know he is dead.’

Evelyn sat in silence, watching him. As she rose to leave, in a gesture that would have seemed foreign to her in the long days of his childhood, she placed a gloved hand over his good hand. Her fingers tightened on his, binding him to her.

Chapter 1

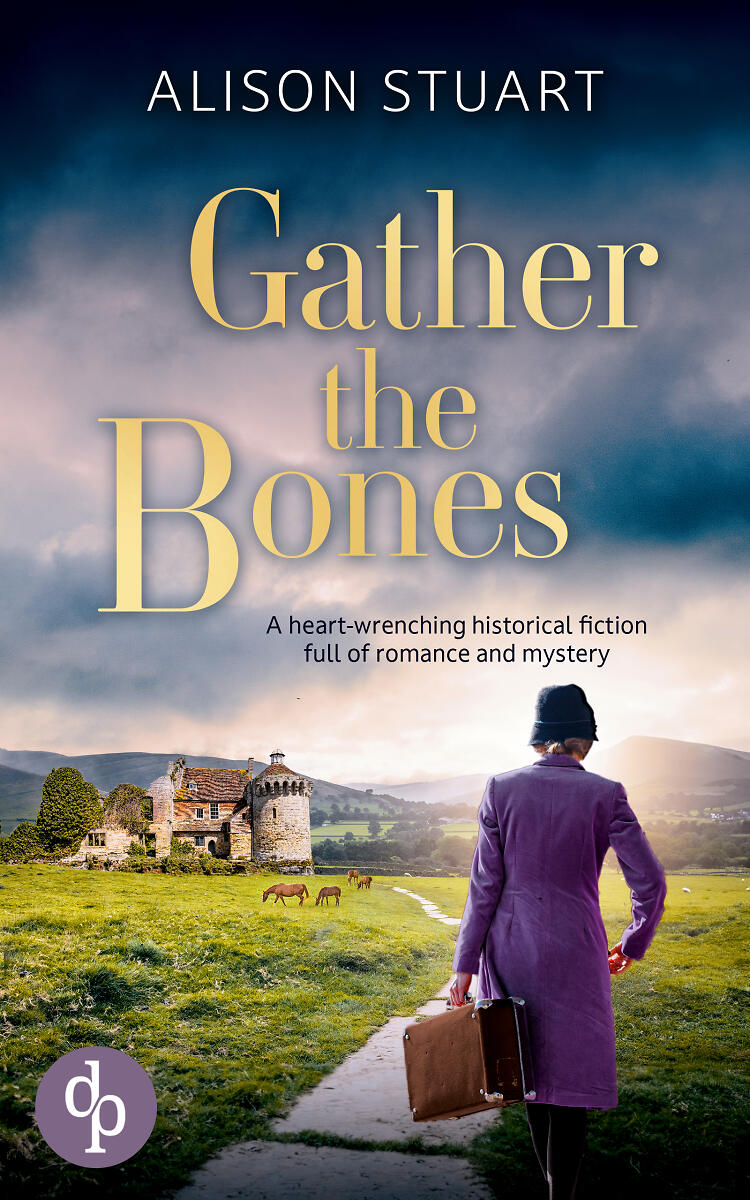

Holdston Hall, Warwickshire July 24, 1923

Helen Morrow took a deep breath, her hand tightening on her daughter’s. She felt a corresponding squeeze, looked down into Alice’s upturned face, and smiled. Why were children so much braver than adults?

She raised the knocker on the old oak door and let it fall. The sound reverberated around the quiet courtyard and she took a step back as the door opened to reveal a small, round woman wearing a spotless white apron over a flowered dress.

Before Helen could speak, the woman’s face lit up with a smile.

‘Mrs. Charles,’ she exclaimed. ‘Welcome to Holdston. I’m Sarah Pollard and you must be Miss Alice.’ She turned a beaming smile on the child before standing aside to usher them both inside the cool, dark hallway and through to a grand room, smelling of beeswax and dominated by a long table and a large fireplace emblazoned with carving. ‘We expected you on the later train. Sam was all set to take the car to the station to meet you.’

‘We caught the bus from the station and walked. Sorry if that caused any inconvenience,’ Helen said

‘Oh, not at all. You’re here and that’s what matters. Come in, come in. Leave your suitcase. I’ll take it up to your room. Lady Morrow is in the parlour. I’ll show you through.’

Helen removed the pins from her hat and set it down on top of the case. She took off Alice’s hat and fussed over the unmanageable fair hair that refused to stay confined in a neat plait.

‘Are you ready to meet Grandmama?’ she asked her daughter, with what she hoped was a confident smile. She didn’t need Alice to see the nerves that turned her stomach into a churning mass of butterflies.

They followed Sarah Pollard’s ample girth across the wide, stone-flagged floor. Helen looked up at the portraits of long-dead Morrows who glared down at her from the wainscoted walls. If Charlie had lived, she would have been the next Lady Morrow and her portrait would have joined theirs, a colonial interloper in their ordered society.

Sarah opened a door and announced her. A slender woman, in her late middle age, her greying hair piled on her head in a manner fashionable before the war, rose from a delicate writing table by the window.

‘Helen. You’re earlier than I had expected,’ Lady Evelyn Morrow said. ‘I would have sent the car for you but you are most welcome to Holdston at long last. And you.’ She turned to the child. ‘Let me look at you, Alice.’

Alice looked up at her mother, her eyes large and apprehensive. Helen gave her a reassuring smile and with a gentle hand in the girl’s back, urged her forward for her grandmother’s inspection.

‘You’re not much like your father,’ Lady Morrow concluded.

Helen could have listed all the ways in which Alice was, in fact, very much like her father, the father she had never known, from the hazel eyes to the way her upper lip curled when she smiled, and her utter lack of concern for her own safety. She must never stop forgetting.

Sarah Pollard bustled in with a tea tray and Lady Morrow indicated two chairs. Alice perched awkwardly on the high-backed chair, her feet not quite touching the floor. Her eyes widened at the sight of the cake and biscuits piled high on the tea tray.

‘I trust you had a good voyage?’ Lady Morrow enquired as she poured the tea into delicate cups.

‘Yes.’ Helen smiled. ‘It was a wonderful adventure. Wasn’t it, Alice? We thought about Cousin Paul as we sailed through the Suez Canal. He must have some incredible stories to tell about the archaeological digs.’

The lines around Evelyn’s nose deepened. ‘If Paul has incredible stories, he does not share them with me, Helen.’

‘But he writes to me and tells me all about them,’ Alice said. ‘Every Christmas and every birthday. Last birthday he sent me a little glass bottle from...where was it, Mummy?’

‘Palestine,’ Helen replied. ‘He said it was Roman.’

‘Does he indeed?’ Evelyn’s eyebrows rose slightly. ‘I am glad to hear he recognises his responsibility to you, Alice.’

‘I’m looking forward to meeting him. They told me he was with Charlie...’ Helen began.

Evelyn stiffened, the teacup halfway to her lips. She set the cup down and folded her hands in her lap. ‘If you are hoping that Paul will shed any light on what happened that day, Helen, then you will be disappointed. Paul was badly injured in the same action and has, apparently, no memory of—’ her thin lips quivered, ‘—the incident.’

Helen caught the sharp edge of an old bitterness in the older woman’s voice. ‘I see,’ she said.

‘You and I, Helen, must mourn over an empty grave,’ Lady Morrow said.

She rose to her feet, walked over to the piano, and picked up one of the heavy silver-framed photographs that adorned its highly polished surface.

‘Did you ever see this photograph?’ She handed it to Helen. ‘I had it taken before Charlie went to France in March 1915. Paul was home on leave and Charlie had just taken his commission.’

The photograph showed two young men in the uniform of infantry officers, one seated and the other standing, a photograph like thousands of others that were now the last link with the dead. Helen had a single portrait of Charlie, taken at the same photographic session, sporting an elegant, unfamiliar moustache and grinning from ear to ear, like an over-anxious school boy, keen to join the ‘stoush’, kill the ‘bloody Bosch’. She felt a keen sense of pain that reverberated as strongly as it had on the day he told her he would have to return to England.

‘I can’t leave them to fight the Huns, Helen,’ he said. ‘Damn it, I have a duty to England.’ The drunken words came back to her and she could see Charlie in the kitchen of Terrala with his arm across her brother Henry’s shoulders, as they celebrated their mutual decision to join the war.

Henry had already enlisted in the Australian Light Horse and Charlie told her a few days later that he intended to return to England to join his cousin’s regiment.

‘Do you think I would leave Paul to uphold the family honour?’ he said.

And he’d gone.

Even as she had stood on the dock at Port Melbourne, the cold winter wind whipping at her ankles, she had known he would not return. She wondered if his decision to go would have been any different if they had known she was carrying his child. Probably not.

She turned from her husband’s smiling face to his cousin, Paul Morrow, the professional soldier, never destined to take the Morrow title until one day in a muddy field outside Ypres had turned his fortune.

The long months of war had already begun to leave their mark and, while he affected a smile, she saw no warmth in his eyes. In normal circumstances, with a strong jaw and good bone structure, it would be a handsome face but he looked tired and drained, and years older than his cousin, although he was older by little over a year.

Yes, Paul Morrow had survived, but at what cost, she wondered.

‘Is Paul here?’ she asked. ‘When he last wrote to Alice, he said he would be in Mesopotamia for the digging season.’

‘The digging season is over for the year and I expect him home in the next few days.’ Evelyn stood up. ‘Now, let me show you your bedroom, Helen. I’ve given you the green room. As the nursery wing is shut up, I thought Alice could sleep in the dressing room. It’s so hard with just the two of us.’ Her voice wavered and she looked past Helen to a point just beyond her shoulder before recovering her composure and continuing. ‘Much of the house is shut up, but Sarah can let you have the keys and you are free to go wherever you want, except my rooms and, of course Paul’s rooms. When he returns, he will also be working in the library.’ Evelyn looked at Alice. ‘Then it will be strictly out of bounds. Sir Paul is not to be disturbed, Alice, do you understand?’

Alice nodded.

***

Upstairs in the green room, Helen found Sarah Pollard unpacking the suitcase.

‘I can do that,’ Helen said.

Sarah looked at her with such appalled surprise at the suggestion, Helen took a step back.

‘You’ve not brought much with you,’ Sarah commented as she set Helen’s silver-backed hairbrush and mirror on the dressing table, along with the photograph of Helen and Charlie on their wedding day.

Helen refused to display the photograph Charlie had sent her of him in his uniform, ready for war. She wanted nothing to remind her of why he had died, even if she did not know the circumstances of his death.

Sarah paused for a moment looking down at the photograph. ‘He was a fine man,’ she said. ‘Everyone he ever met liked him.’

Helen’s throat constricted and to distract herself, she looked around the room. The faded green curtains and bed coverings on the old half-tester bed gave the room its name. A small bookshelf of leather-bound books stood against one wall and the heavy mahogany dressing table dominated the other. A door led through to the room Evelyn had called the dressing room, where an iron bedstead, covered in a pink eiderdown, had been set up for Alice.

Helen stooped to look out of the low window at the view across the parkland, at the unfamiliar richness of the English countryside. Summer wrapped the world in a thick green plush, unlike home where summer bleached the land and everything living in it.

‘Can we go exploring now?’ Alice pleaded.

‘Supper will be at six,’ Sarah said. ‘Her ladyship eats a main meal at lunchtime and takes only a light supper. She said to tell you there’s no need to dress.’

Helen smiled. ‘That’s fine.’ No one dressed except for the most formal meals at Terrala.

Sarah handed over a bunch of keys before leaving and Helen and Alice started at the top of the house, opening all the doors and peering into the dark, dusty rooms. The old house was built in the shape of a letter C with a front wing facing the main entrance, the side wing dominated by the Great Hall through which they’d entered, and the back wing which housed the kitchen on the ground floor and more bedrooms above. They found the nursery and Alice gave a squeal as she rushed toward a magnificent dollhouse.

‘Do you think Grandmama will let me play with it?’ she asked.

‘I am sure she will,’ Helen said, taking the opportunity to search a bookshelf for suitable books for Alice. She was delighted to discover the complete set of books by E. Nesbit. There seemed to be books in every room in the house.

‘Daddy told me there were secret hidey-holes and passages,’ Helen said, caught up for a moment in a childish marvel at the antiquity of the house.

Alice’s eyes shone. ‘Did he say where?’

Helen shook her head.

‘Perhaps Grandmama or Uncle Paul will know,’ Alice said.

When Paul Morrow’s birthday and Christmas letters had begun arriving for Alice, Helen had decided to accord this distant, but important, relative an avuncular title. It seemed easier for a small child to comprehend than Cousin Paul and, knowing the close bond between Charlie and his cousin, it also seemed more appropriate.

On the upper floor of the house, Helen and Alice passed the solid, oak door that Evelyn had pointed out as Paul Morrow’s rooms occupying the corner between the front and the side wings. They also walked through a gallery lined with faded tapestries and paintings, a large airy parlour over the old gateway into what would have been the inner courtyard, and then into the passage leading to Lady Morrow’s rooms at the end of the wing. A narrow, winding staircase at the end of the passage led them down to a locked oak door. Helen tried most of the keys on the ring until one massive iron key turned reluctantly in the lock.

When the turn of the handle still did not shift the ancient door, Helen leaned her shoulder against the wood and pushed. The door creaked reluctantly and opened onto a large room dominated by two massive bookshelves taking up the spaces on either side of an old fireplace. A long, low window looked out over the moat to the driveway. Ancient framed maps and paintings of Holdston Hall crowded the remaining wall space. Several smaller family portraits were dotted among the maps and watercolours, including two head and shoulders studies of a man and a woman painted during the Georgian era and a couple of later Victorian models with severe, frowning faces.

Helen walked over to the Georgian pair and studied them closely. She could see at once that they had been painted by different hands, probably at different times, and yet they had been framed identically and hung together as if in life they had belonged as a pair.

The man had obviously been a Morrow. Like the other portraits of the Morrow forebears, dark hair tumbled over his handsome aristocratic brow and he glared at the artist, his stiffness emphasised by the high collar of a scarlet uniform. Charlie’s fair hair, inherited from his mother, made him quite a cuckoo in the family portrait gallery.

In contrast to the formality of the male portrait, the woman beside him glowed with life. A fierce intelligence burned from her light grey eyes. A tangle of chestnut curls framed her face and her mouth lifted in a half smile as if any moment she would burst into laughter. She wore a green gown that exposed a great deal of décolletage in a manner fashionable in the early part of the nineteenth century and no jewellery except a slender gold chain, with a locket hanging from it, nothing more than a blur of gold under the artist’s brush.

Helen shivered and pushed the windows open, admitting a breeze that carried with it the waft of warm grass and the sounds of the country—birds and the distant hum of a steam engine driving a threshing machine.

Along with these comfortable, familiar sounds drifted another faint sound, a whispering, a woman’s voice half-heard, the words indistinct and undecipherable.

Helen frowned and tilted her head to listen, turning back into the room.

‘Can you hear something, Alice?’ she asked.

Alice looked up from turning an old globe on the table.

‘No,’ she said.

Helen looked around. The whispering seemed to come from within the room, not through the open windows. She stood transfixed, staring at the two wing chairs by the fireplace. The whispering grew more insistent, more urgent. Wrapping her arms around herself, Helen gripped the sleeves of her cardigan. The back of her neck prickled, and she held her breath for a moment.

As she took a step toward the chairs, the whispering ceased and she let out her breath and straightened her shoulders before crossing to the windows and pulling them shut.

‘Come on, Alice,’ she said. ‘We’ll be late for supper and I don’t want to annoy your grandmother on our first day.’

Chapter 2

In the morning, Helen induced a reluctant Alice away from the dollhouse with the promise of a visit to the village shop. Rather than follow the drive, they cut along a neglected path that led from the house to the village church. Their feet crunched on the weedy, broken gravel and the hinges of the small gate into the churchyard squealed in protest as Alice pushed it open.

Walking through the gravestones to the church, they paused at one or two to read the inscriptions and marvelled at their age. In the cool interior of the church, Helen stood still, allowing her eyes to become accustomed to the gloom. She was fascinated by old buildings. No building in Mansfield was older than fifty years, and to stand in the nave of a church where men and women had worshipped for centuries filled her with awe.

They wandered down the side aisle of the church past carved stone knights and their ladies resting on their tombs, and walls covered in memorial plaques, mostly to long-dead Morrows. Beside the choir stalls in plain view of the nave, a bright brass plaque, headed In memory of those of this parish who died in the Great War 1914-1918, caught Helen’s eye.

Her own town had subscribed to a public fund and erected a solid memorial in the centre of the town, the plinth inscribed with the names of the fallen of the Mansfield district. She scanned the list of about twenty names. This simple plaque was no different; it could have been the same names, the same young, hopeful faces.

Captain Charles Morrow MC headed the list.

She swallowed. Seeing his name so starkly written made it all so real. The fact it did not appear on the Mansfield war memorial had been a matter of some dispute with her father who chaired the public subscription to raise funds for the Memorial. Treacherously, her brother had sided with their father pointing out that whatever their personal feelings for Charlie, he had not fought with the Australians.

‘Look, Alice,’ she said. ‘Here’s Daddy’s name.’

Alice stood beside her, slipping her hand into her mother’s. They stood hand in hand, looking at the plaque and allowing the silence of the old building to engulf them.

‘Can I help you?’

Both Helen and Alice jumped and Helen turned to see the vicar, a middle-aged man with greying hair, in a dog collar and long dark robe, watching them from behind heavy horn-rimmed spectacles.

‘I’m sorry if I disturbed you.’ The vicar blinked behind his spectacles as he looked up at the memorial plaque. ‘I shall leave you to your prayer.’

‘It’s all right, Vicar. It was just something of a shock to see my husband’s name here. I’m Mrs. Morrow,’ Helen said.

‘Of course, I quite understand. Welcome to Holdston, Mrs. Morrow. My name’s Bryant.’

Helen dutifully shook his proffered hand. ‘This is my daughter, Alice,’ Helen said, placing her hands on Alice’s shoulders.

‘You are most welcome too, Miss Morrow,’ the vicar said. ‘I have a daughter your age who would love to meet you. My youngest,’ he added, looking up at Helen. ‘The others are all away at school now and Lily gets terribly lonely.’

‘That would be wonderful. It is a little quiet for Alice up at the Hall and she would be glad of a playmate.’ She turned back to look at the church. ‘It’s a dear little church.’

The vicar beamed with pride. ‘Twelfth century, if not older, I believe. Indeed, the Manor of Holdston is mentioned in the Domesday book.’

‘I can’t imagine what it must be like to live in the same place as my ancestors have lived for all those centuries,’ Helen said. ‘Where I come from, there’s nothing older than sixty years.’

‘Ah, you’re an Australian, if I remember rightly? Young Mister Charles met you when he went out to Australia to work as a...’ He searched for the word.

‘A jackeroo?’ Helen suggested.

‘Good heavens, what a strange expression. He always wrote so fondly of Australia. We feared he may never come home. You know there are six centuries of Morrows in the family crypt under the church? They’re all there except, of course, young Charles...’ He broke off. ‘I’m sorry. I’m sure you don’t need to be reminded.’ Turning to Alice, he changed the subject. ‘There is a story that a secret tunnel runs from the house to the church.’

‘Why?’ Alice asked.

He shrugged. ‘I believe the Morrows of the sixteenth century kept getting their religion wrong, Catholic when they should have been Protestant, Protestant when they should have been Catholic. I’m sure a secret tunnel would have been very useful in those circumstances. They say Charles II used it when he fled the battle of Worcester, but of course, every old house in this area has a Charles II story so I have my doubts as to its credibility.’ He looked at Helen. ‘Is Sir Paul home yet?’

Helen shook her head.

‘I do enjoy my chats with him. He was in Palestine last year, you know? If he’d had the chance to get a proper university education, there’s no telling what he would be doing now, but the war...’ He shrugged. Helen had heard it before. The war accounted for so many things that should have happened. ‘Of course, his work takes him away from Holdston and he doesn’t have the time for the church and the estate. Your own dear husband...’ The church clock struck eleven and he glanced at his watch. ‘Is that the time? Mrs. Morrow, Miss Morrow, if you’ll excuse me, I have a sermon to write. Shall I see you in church on Sunday?’

Helen smiled. ‘Of course.’

Helen watched as the vicar entered the vestry, closing the door behind him. She gave the memorial plaque one last look and walked gratefully into the warmth of the summer day.

***

Carrying magazines and a bag of humbugs procured from the village shop, Helen and Alice strolled back to the big house. From the driveway, Helen could see the stable courtyard where a man washed a large, old-fashioned Rolls Royce. She looked at Alice and they turned down the driveway toward him. He straightened when he saw her, wiping his hands on a cloth.

‘Mrs. Morrow, Miss Alice,’ he said. ‘Sorry we didn’t meet yesterday. I would have brought old Bess here to meet you at the station. I’m Sam Pollard.’

‘How do you do, Mr. Pollard,’ Helen said with a smile.

‘Call me Sam or Pollard,’ the man said. ‘Mr. Pollard just doesn’t sound right.’

Alice opened the packet of sweets. ‘Would you like a humbug?’

‘Don’t mind if I do.’

Pollard sat down on the running board of the car and selected a sweet from the bag. Helen leaned against the mounting block.

‘Is Lady Morrow going out?’

Pollard shook his head and shifted the humbug to his cheek as he replied. ‘No. These days, if her ladyship goes up to London or into Birmingham, she takes the bus or the train. This old girl,’ he patted the Rolls affectionately, ‘doesn’t often get much of a run. The Major thinks we should sell her and get something smaller.’

‘It’s a beautiful car,’ Helen said.

‘I remember when Sir Gerald first bought old Bessie here. The whole village turned out to watch him drive it. He took all the village children for rides. He was a good man, Sir Gerald.’ Sam’s lips tightened. ‘Master Charles’s death broke his heart and to see the old place now—’ he looked up toward the hall, ‘—falling down around our ears and not the money to fix it. If Master Charles were here...’

Helen looked up at the house. It seemed clear, in the opinion of some people, that the wrong Morrow had come home from the war. If Charlie had ever intended to return to Holdston, he had not shared his thoughts with her, but at the time of his death his father had still been alive and inheriting Holdston had seemed a distant problem. They had made plans for a future together in Australia.

‘Mummy.’ Alice’s excited voice came from the stables and she peered around the door. ‘Come and see the horses.’

Helen straightened and walked over to the stables, pausing in the doorway to breathe in the familiar smell of warm horse and hay that reminded her of the stables at Terrala.

‘Used to have the best bloodstock in the county.’ Sam Pollard had followed her to the stables. ‘All gone now except for her ladyship’s old hunter, the Major’s grey, and a couple of trap ponies.’

Alice stood beside one of the stalls stroking the nose of an elegant chestnut with a white star. Sam rummaged in a sack by the door and handed a couple of withered carrots to her. She held them out on her palm, giggling as the horse’s soft nose tickled her.

‘This ‘ere’s Minter.’ Pollard ran a loving hand down the nose of the chestnut. ‘Her ladyship’s hunter, only she don’t ride anymore on account of her bad hip. Pity. He’s getting old and lazy, aren’t you?’ Minter’s ears swivelled, as if aware he was being talked about in disparaging tones.

Helen dipped her hand into the oat bin and offered some to Minter, who snaffled them appreciatively. She patted him on the graceful curve of his neck.

‘He’s beautiful,’ she said. ‘I miss my horses.’

‘If you’ve a mind to it, her ladyship would probably have no objection to you taking Minter out for a ride sometime. The old boy could do with the exercise.’

‘What about me?’ Alice asked. ‘Can I ride one of the trap ponies?’

Pollard shook his head. ‘I wouldn’t like you to do that, Miss Alice. Awful mean those ponies can be.’

Helen put a hand on her daughter’s shoulder, seeing the child’s disappointment in the droop of her mouth. ‘Never mind, Alice, I am sure we will find something suitable for you.’

Pollard moved to the next stall and stroked the nose of a beautiful dappled grey with a dark mane and tail.

‘And this here’s Hector, the Major’s horse.’

‘Does the Major ride much?’ Helen asked.

‘When he’s home,’ he said. ‘He’ll take him out most mornings—if his leg isn’t botherin’ him too much. Fine rider, the Major. He should have joined the cavalry, but old Sir Gerald insisted he joined his father’s regiment.’

‘His leg?’

‘Aye, smashed it the night...’ Pollard stopped. ‘He was wounded you know.’

Helen nodded. ‘So I’ve been told.’

Pollard cleared his throat and Helen, deciding against pushing the man with any more questions, repeated the exercise with the carrots, handing a couple to Alice who fed them to Hector. Minter looked over expectantly and nickered at her.

‘You’ve had your share,’ Alice told the horse.

‘And you, young lady, have some lessons to do this morning,’ Helen said, steering her daughter toward the stable door.

Alice looked over her shoulder at Pollard. ‘Can I come and visit the horses?’

The man smiled. ‘Any time, lass.’