Chapter One

I’m not ashamed to say that I screamed when the body fell at my feet. In fact, it almost fell on my feet, but I managed to stagger backwards. Instead of receiving the full force of impact, my one pair of decent shoes received a stippling of blood across the toes, spattering the leather in a string of glossy red beads.

There was an exclamation and I looked up, furious.

“Sorry! Sorry, miss.” One of the men I’d seen working on the estate hurried towards me, his shotgun hanging loosely from his hand. “I didn’t see you there.”

By now he had reached me and we both looked down at the body of the magpie, its black and white wings a monochrome splash against the dusty grass.

By now, I hoped I’d recovered a little poise.“You startled me,” I said inadequately, trying to stop my voice from shaking. The man hung his head a little. He was younger than I’d first thought, about thirty-five, his skin tanned and weathered from all the work he did outdoors. “What on earth are you doing, shooting magpies, anyway?” I added in a more normal tone.

“Ah, they’ll take the young chicks if they find them, miss,” he said. He stooped and picked up the body of the bird. “Not as bad as the kestrels, though, but we’ve still got orders to shoot them if we see them around the breeding grounds.”

“I see,” I said. I looked at my shoes again and tutted.

The man almost blushed.“Let me help you there, miss,” he mumbled and bent and tore up a handful of grass. Before I could stop him, he had wiped the blood from the toes of my shoes.

“Thank you,” I said, my own cheeks now scarlet. I was half thinking that he’d done that just to get a good look at my legs. He clambered back onto his feet and stood back a little, to let me pass by.

“You work up at the kitchens, don’t you?” he said, just as I was walking away.

“Yes, I’m the undercook,” I said with dignity and perhaps just a touch of ‘so I’m higher in the servants’ hierarchy than you’ in my voice.

I’m not sure he got the message. He grinned and said, “Well, I’ll have some lovely birds for you to cook up soon, miss.”

I said nothing but gave him a cool nod and went on my way.

Though I was supposed to be hurrying back – my afternoon off ended abruptly at four o’clock – somehow I just couldn’t seem to make my feet move faster than a dawdle. I followed the footpath that skirted the edge of the Merisham estate, winding through the oak and beech trees. Halfway along the path, I had to clamber over a stile, a little awkwardly in my long skirt, before the path led me across a field, past the chattering little brook that crossed the corner, over another stile and finally onto the road that eventually led to the back gate of the lodge.

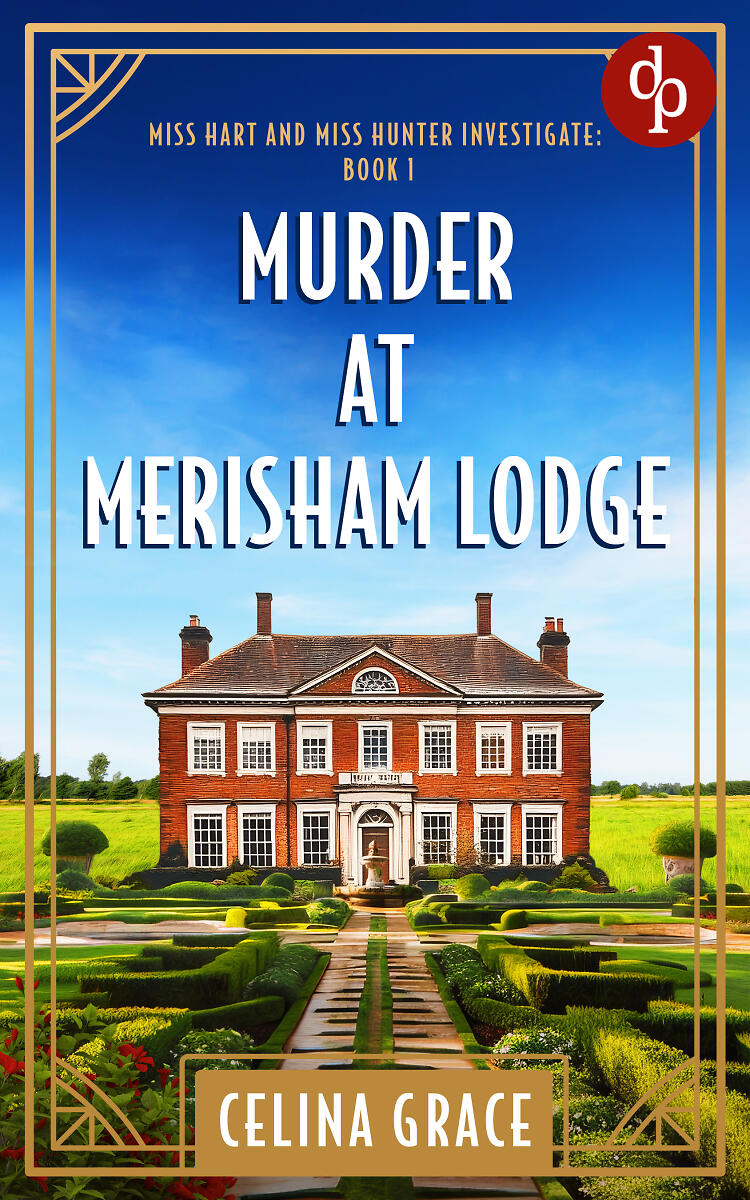

Merisham Lodge had been in Lord Cartwright’s family for over a hundred years. My friend, Verity, had told me so when she persuaded me to apply for a position here.

“It’s a big old place,” she told me and then added hastily after seeing me flinch, “but not that old – not as old as Asharton Manor. The family keeps it for shooting parties and for their summer residence, normally. They’re going up a little early, this year, and so they’ll need a full set of staff…”

“I don’t know, V,” I said. “Is it very isolated? I don’t think I could stand that again.”

Verity hastened to reassure me. “It’s only a mile from the village, and you’re less than five miles from Buxton. It’s nothing like Asharton Manor, believe me, Joan.”

“Hmmm,” I said, not entirely convinced, but then I trusted Verity. After all, what other choice did I have? It wasn’t as if there were hundreds of jobs out there for a partly-trained kitchen maid, or at least not so many in places that I would actually want to work. If I took a position at Merisham Lodge, I’d be working in the same house as Verity. We might even get to share a room. It wasn’t as if I particularly liked the place where I was working at that time;it was a doctor’s house in Kilburn. It had been one of the places I’d applied for in a panic after I left Asharton Manor.

“The food’s good, and you get a decent amount of time off,” Verity said encouragingly.

“What about them?” I didn’t have to elaborate any further. Verity knew whom I meant.

“Oh, he’s a bugger,” she said cheerfully. “And Madam’s just as bad. But believe me, Joan, you won’t come into contact with them very often, so you don’t have to worry.”

“Hmmm,” I said once more, but that was just for show. By that time, I’d already made up my mind.

My first sight of the lodge hadn’t exactly been encouraging. I’d met the housekeeper, Mrs Anstells, in London to be interviewed. I had actually met her before, as Verity had worked for the family for years. Of course, Verity had also put a good word in for me, and I had a good reference from my last position at Asharton Manor (probably the only positive thing to come out of the whole ghastly experience). I was pleased but not greatly surprised when I was offered the position. I’d taken the train up the following week and prepared to walk the couple of miles from Merisham Station to the lodge. My trunk hadn’t been that big but it seemed to get heavier and heavier, the further I plodded. Of course it would start raining before I got more than fifty yards. I trudged on through the downpour, thinking what a fine sight I’d look when I actually got to the lodge; more like a drowned rat than a professional servant.

As I walked, I remembered the first sight I’d had of Asharton Manor and what a shock it had been. It had seemed like a palace to me, newly arrived from grey old London. What a fine sight it had been–and how deceptive the appearance was. It wasn’t particularly cold, despite the rain, but I still shivered at the memories.

By then I had become more accustomed to fine houses, the lodge didn’t look all that awe-inspiring, especially as I could only glimpse it through a curtain of falling rain. It looked handsome enough, I suppose; solid, well-built, and surrounded by some fine lawns and well-tended gardens. I had walked on round the back, of course, and rang the rather rusty bell affixed to the wall by the back door, wondering what my fellow servants would be like.

Today, the house looked very different in the spring sunshine. In high spirits, after my walk and the few hours I’d had to please myself, I wiped my feet on the boot-scraper by the back door and went on into the kitchen.

“Oh, Joan, you’re back. Good.” The cook, Mrs Watling, darted back and forth between stoves, as was her wont. I’d never met someone quite so blessed with energy – she made me, some twenty years her junior, feel quite tired. “Had a nice afternoon?”

“Lovely, thank you,” I said with feeling. I liked my job well enough, and Mrs Watling was a good and patient person to work for, but all the same, a job is a job and after a few hours of freedom, it was always rather melancholy to come back to reality with a bump. I tried to shake off the feeling. It helped that the kitchen windows were flung wide and the sunshine and fresh spring air flooded through into the kitchen.

As kitchens go, it was actually quite a pleasant place to work. The whole room had been modernised some years before and we had, wonder of wonders, a gas stove as well as the range. The ‘pop’ of the gas as it lit had scared me stiff at first – I was sure we’d all be blown to kingdom come – but as was usual, it was amazing how quickly I got used to it and soon became rather blasé about striking a match and lighting it. The floor was tiled with smooth red ceramic tiles, such a pleasant change from the usual pitted and marked flagstones that needed a hearty scrubbing every day before they looked clean.

“Joan, go and change, there’s a good girl. They’ll be wanting tea at half four, and I’ll need you to cut sandwiches.” Mrs Watling scraped a load of carrot peelings into the stock pot with a flourish. “There’s the ginger cake that needs eating as well. That and scones should be enough, I would have thought.”

I nodded obediently and made for the servants’ stairs. Those stairs irritated me, as they had done in every house I’d been in that had them. It wasn’t enough that we had to run around after these people, catering to their every whim and often receiving nothing but scorn in return, but that we had to do all that whilst remaining as invisible as we possibly could. I mean, God forbid that we were able to use the hallowed steps of the main staircase. I stomped on upwards, my good mood of the morning dimming more the further up the stairsI went.

One of the good things about working at Merisham Lodge was that I had indeed been able to share a room with Verity. It wasn’t the way things were normally done, the undercook and a lady’s maid sharing a room, but, in her usual way, Verity had charmed Mrs Anstells around into thinking that it was a good idea. I wondered whether Verity would be there now, but it didn’t seem likely. Verity was lady’s maid to the daughter of the house, Dorothy, and would very likely now be cleaning her jewellery or mending her underwear, or making up a beauty potion for her mistress to use later. I knocked on the door of our room, just in case, but only silence met me. Never mind. I’d see Verity at dinner time, and we’d be able to have a good old chinwag then.

I hung up my skirt and blouse and pulled on my uniform. Standing in front of the little mirror,which hung on the far wall above the narrow table we used as a dressing table, I peered at my dim reflection. I tried to scrape back my hair until it was entirely hidden under my cap. It was difficult, as I had to virtually festoon my very thick, long hair with hairpins before it consented to do what it was told. As always, I wondered whether I would ever be bold enough to have it cut short, like Dorothy Drew wore hers, in a daring flapper bob. But then, when you’re rich and young and beautiful, you can carry off a style like that. “Dorothy would look good in an old sack,” I remember Verity saying once, and I had to agree. Fleetingly, I wondered whether Dorothy would be considered quite so beautiful if she hadn’t been quite so rich.

My hair safely stowed away under my cap, I picked up a clean apron and a clean pair of cuffs and made my way back downstairs, hurrying as I caught sight of the clock. I hastened into the kitchen, washed my hands, and began sawing at a loaf of bread. Cucumber sandwiches and meat paste, perhaps…Mrs Watling backed out of the larder, her hands full of eggs, and gave me an approving nod.

“Don’t forget the ginger cake,” was all she said before she sped off in the direction of the wine cellar.

The sandwiches cut, the ginger cake placed on a cake tray, and the jam and butter carefully decanted into separate pots, I hastily arranged the scones on a plate and added the linen napkins. I could hear the drawing room bell jangling away out in the passage but nobody appeared. Cursing under my breath, I went out in the corridor, wondering if I should shout. Where was everybody? I knew Nora, one of the two parlourmaids of the house, was out on her afternoon off – I’d even seen her in the village and we’d exchanged smiles from across the street – but Nancy should have been here. It was almost quarter to five and the bell for the drawing room was even now bouncing up and down on its hook. I cursed a little louder, whipped off my dirty apron, and picked up the tray.

I pounded up the back stairs to the ground floor, manoeuvred my way through the door to the hallway, and then hurried along towards the drawing room, tray chinking and clinking in my hands. I caught sight of myself in the enormous gilt-framed mirror that hung on one side of the hallway and groaned inwardly. I was scarlet in the face, tiny beads of sweat garlanding my nose. While the apron I’d discarded in the kitchen had kept the worst of the muck off my dress, there were still enough spots and splashes and stains all over me to make me look like something that could have been dragged up from the cellar.

Nobody will even notice you, I told myself reassuringly, and sure enough, once I’d knocked and was bid to enter, I might as well have been invisible. I set the tea tray on the round table by the window, just as it was always placed for this daily ritual.

The whole family was gathered in the drawing room: Lord and Lady Cartwright, Lord Cartwright’s son, Duncan, and Lady Cartwright’s daughter, Dorothy. Lord Cartwright’s social secretary, Rosalind Makepeace, was also there, sitting quietly by herself over to one side of the room. I looked at her quickly before looking just as quickly away. She intrigued me: she was good looking, in a way that was the antithesis of Dorothy Drew’s showy beauty. Rosalind’s face had something more subtle. Still waters run deep was the phrase that occurred to me then. I thought she had a kind of foreign look to her, without being able to say exactly what I meantby that. Perhaps it was her black hair, glossy and smooth as jet, or the sharpness of her cheekbones. Duncan Cartwright was seated next to Rosalind, but he was turned quite sharply away from her, leaning towards Dorothy. As usual, they were laughing and joking together, the cigarettes in their hands sending up twining blue tendrils of smoke that partly veiled their faces. He was good-looking, I thought, that was undeniable, but all the same, I didn’t much like his face. There was something a little cruel around his mouth, and while he seemed to be always smiling, it never seemed to reach his eyes.

Lady Cartwright approached the tea table. She was a tall woman, with a figure that could have, from the back, been taken as that of a girl thirty years younger. From the front, the illusion fell away. She was hard-faced, with a manner that was superficially charming but – as all we maids had experienced – a temper beneath it that could be quite frightening.

I braced myself to speak to her. “Will that be all, my lady?” I murmured in what I hoped was the right respectful kind of voice.

“Yes, yes,” she said impatiently, dismissing me. As I left the room, Albert, one of the footmen, hurried past me into the drawing room. Good, he could serve them, because I certainly wasn’t going to. Thankfully, I pulled the door shut behind me and hurried back downstairs to the kitchen. At least there I didn’t have to face any of them.

There were only three of them to dinner that night, Lord and Lady Cartwright and Duncan, so that made for a relatively peaceful afternoon’s work for me and Mrs Watling. I had been hoping to be able to have a chat with Verity at the servants’ evening meal, but she’d virtually bolted her food and rushed back upstairs, signalling over the table to me with her eyebrows as she left the room. Long practice had made me adept at reading Verity’s mobile face. Those eyebrow movements meant that she had a long night’s work ahead of her – damn it to hell, I heard her voice say inside my head, and grinned – probably because Dorothy was dining out, and Verity would have to wait up for her.

Normally, it was me who got to bed late, unless Verity had to do what she was doing this evening. It was quite a novelty for me to be sitting up in bed, reading my book, with Verity’s bed on the other side of the room empty. I’d turned it down for her and slipped one of the stone hot water bottles between the sheets. That was the first thing she remarked on when she finally came into the room at past midnight, when I was virtually nodding off over my book.

“Oh, bless you, Joanie, that’s so kind of you.” Verity sat, or rather collapsed, onto the edge of her bed. Her face was pale with fatigue, the normal vivid colour of her hair somehow dimmed. She rubbed her face. “God, I’m all of a heap.”

“It’s so late,” I said, yawning. “It’s too bad of Dorothy to make you wait up so late.”

“Oh, I’m used to it by now,” Verity said, beginning to strip off her clothes. “I’m not going to wash, I’m too bloody tired.”

“Where had she been tonight?”

“A party somewhere.” Verity pulled her nightdress on over her head and sat down again to roll her stockings off. She gave a tired giggle. “She rolled in just as drunk as a lord. She’ll have such a head in the morning.”

“Humph.” I waited until Verity had got into bed and then turned down the oil lamp. “It’s all right for some, isn’t it?”

I could hear the bedsprings of Verity’s mattress clink and chime as she got comfortable. “Well, who’s to say we can’t do the same? When’s your next day off? If it coincides with mine, we could go into town. Have cocktails.”

I laughed. “Don’t be ridiculous, V.”

I could hear her giggle again faintly and then give a much bigger yawn. “Yes, I know. Lord, I’m tired. I must sleep. Night, Joanie.”

“Good night.” I lay there for a moment, staring into the blackness. I always tried to stay awake a little longer if I could – it was the only time I ever had peace and quiet and time to try and organise my thoughts – but, as usual, it was a hopeless task. The last thing I remembered was the peaceful sound of Verity’s breathing before sleep claimed me.

Chapter Two

It was eleven o’clock by the time I got to finally sit down the next morning. I’d cleared away the last of the breakfast things and seated myself at the table with a pile of potatoes and a vegetable peeler. I didn’t mind peeling things – it was monotonous enough work but you could think about other things at the same time. I was pleased when Verity appeared in the kitchen doorway with a pile of clothing in her hands.

“Sewing?” I asked.

Verity nodded. “I’ve been putting it off, but now we can sit and chat, it won’t seem so bad.”

“I’ll make us some tea,” I said, putting aside a half peeled potato and getting up.

Just as I was filling the kettle, there was a knock at the kitchen door. Wiping my hands on my apron, I went to open it.

There was a man outside, a stranger. He was rather smartly dressed for a tradesman and carried his hat in his hand. He was young, probably not more than twenty-five or so, and rather brown.

I raised my eyebrow interrogatively. “May I help you?”

The man shifted from foot to foot. By this time, Verity had looked up from her mending and when she saw who it was, she jumped up with an exclamation.

“Good morning, sir,” she said, rushing up to stand beside me at the door. “How may we help?”

So, he merited a ‘sir’, did he? I let Verity push forward a little.

“Hello, Verity,” said the man. “I’m just here to see the mater. She’s not expecting me.” For a moment, he looked almost shifty. “You couldn’t show me up to my room and let the old girl know I’ve arrived, could you?”

Verity bobbed a curtsey. “Of course, sir. Do come with me.”

I watched her whisk the man through the kitchen and out to the passageway beyond. After a moment, I heard what was probably their feet walking overhead as they made for the main staircase.

I sat back down at the table again, frowning. Who on earth had that been? Clearly he was some part of the gentry – perhaps even part of the family. So why in the world had he come to the servants’ entrance and not rung the doorbell of the main house, as anyone else of that status would? It was a puzzle that I turned over in my head as I picked up my peeler and slowly began to divest the potatoes of their jackets.

I’d almost finished by the time Verity came back again.

“Who was that?” I asked as soon as she’d sat back down.

She rolled her eyes. “That was Lady Eveline’s son, Peter Drew. He’s the son of her first husband. Dorothy’s brother.”

“I haven’t seen him before,” I commented, beginning to slice the peeled potatoes.

“No, well, he’s not often here. He and his mum don’t get along brilliantly. She thinks he’s a – well, a wastrel. He only turns up here when he needs some money.”

“And Lady Eveline gives it to him?”

Verity smiled cynically. “Not without a screaming row, normally.”

I raised my eyebrows. “Is he married?”

“No. Bit of a scoundrel, I think, judging from some of Dorothy’s remarks.” Verity bit off the thread she was holding. “Sounds like he takes after his father.”

“In what way?”

“Well, he was a bit of a rogue, by all accounts. Dalliances with actresses and so forth.” I raised my eyebrows again and Verity grinned. Her family was connected with the theatre and she knew quite well what some people thought of those in the acting profession. “As it was,” she went on, “He got drunk and fell in front of an omnibus one night and that was that. Of course, it was sad for Dorothy and Peter. I mean, he was their father.”

I tipped the sliced potatoes in a bowl of cold water and shook the salt cellar over it. “So Duncan Cartwright isn’t Lady Eveline’s son?”

Verity rolled her eyes. “No, Joanie, you know that. Remember? Lord Cartwright was married before and his wife died, about a year before he married Lady E.”

It was true Verity probably had told me that before but, to be honest, I had little time to worry about remembering the ins and outs of the family. It wasn’t as if I came into contact with them much (thankfully), unlike Verity. I suppose she had to know who was who and what was what.

Verity began neatly folding the mended clothing. She had a very steady hand and could make tiny, neat stitches, something I’d never managed to master. She’d trained herself in mending lace, a useful skill for a lady’s maid to have, but then Verity was a fiend for self-improvement. “I’m a lifelong student,”she told me once, when I caught her poring over an encyclopaedia in the library at Asharton Manor.

Asharton Manor. I caught myself in an involuntary shudder, something that often happened when I remembered the accursed place. It had been cursed, I was sure of it. I wasn’t just being fanciful. I remembered the clearing in the forest and the haunted feel of the woods surrounding the house. I remembered, too, the pale shape of the body in the bed, the greyish tinge to her skin, as if she’d walked through a room full of cobwebs.

Verity looked up sharply. “Joan? Are you all right?”

I shook myself back to reality. “Fine. I’m fine.” It wasn’t like me to brood, but sometimes the memories caught me unawares. “Fancy another cup of tea?”

“Ooh, yes. That would be lovely.”

I put the kettle on the hob and lit the gas. “How was Dorothy’s head this morning?”

Verity chuckled. She had a lovely, gurgling laugh that always made you want to join in. “Sore! I had to fetch her aspirin by the pound.” She finished folding the clothes and began to stack them in a pile. “I think she’s got a new beau. She had a card from a Simon Snailer in her handbag and she never keeps cards, normally.”

“’Simon Snailer!’” I poured out the tea for us both. “She won’t want to marry him. Imagine being Mrs Dorothy Snailer.”

We both laughed at that. “What’s he like?” I asked, curious despite myself.

“No idea. I haven’t accompanied her out for a bit, I don’t know who she’s been seeing lately.” She picked up the stack of clothing. “Anyway, I’d better get these back upstairs and put away.”

“Have your tea first.”

“Of course. You do look after me well, Joanie.”

“Someone’s got to.” We smiled at each other. Verity and I had met when we were both small girls, in the orphanage where we both grew up. She was from a high-born family fallen on hard times; I most definitely was not. We had liked each other from the start and now she was my oldest and dearest friend.

I drained my cup and washed it up. Verity said goodbye and went out with the pile of clothing. I began to prepare the soup for the evening meal, quite a complicated one with white fish and various vegetables and herbs. I think I was quite content then, thinking about nothing more than the work I had to do but knowing that it was all under control so far. It was a sunny day and beams of light poured through the large windows, such a pleasant change to some of the kitchens I’d worked in. Mrs Watling came in from her trip to the village and nodded approval at seeing me well employed.

Once the soup was well underway, I stood back and stretched a little, easing my aching back. It was then I noticed a white object over on the floor by the door. Verity had dropped one of Dorothy’s chemises as she left the room.

“I’m just going to take this up to Verity,” I told Mrs Watling, who nodded again.

“You’ll need to make the stuffing for the duck, but that can wait until you get back,” she said, whisking in and out of the pantry with her hands full of tins and jars.

I took the servants’ stairs, of course. Dorothy’s room was on the second floor, so at least it wasn’t too much of a climb, unlike at the end of the day when I had to trudge up to the attic floor on tired legs. The servants’ door to the second floor was one of those concealed ones, right at the end of the corridor. I closed it behind me quietly and made my way down the hallway.

Raised voices behind one of the doors made me pause. I realised they were coming from Lady Eveline’s room – it was her talking, loud and hard, and a man’s voice too. I didn’t recognise it for a moment and then I realised it was her son, the one who’d arrived this morning, Peter Drew.

“You’re just like your father,” Lady Eveline said. There was a sneer in her voice, apparent even to me on the other side of the door. “Lazy, useless, and grasping. If you think I’m going to bail you out yet again, you’ve got another think coming.”

Peter spoke then. “I know you’ve never had much opinion of me, Mother. Not that I can’t say the feeling’s mutual –”

“How dare you speak to me like that?”

“How dare I? Oh, I dare, all right, mother. And if you’re not going to help me, I can think of a few people who might be very interested to hear one or two things about you –”

I was holding my breath and the blood thumped in my ears. I was dying to hear what Peter would say next but I never got the chance. I heard a door opening down the corridor and nearly jumped out of my skin. Hurrying past the door, I swerved into the next room, which was Dorothy’s.

Verity was there, folding clothes into the chest of drawers by the adjoining wall. She gave me a wry glance as I panted into the room.

“Going at it hammer and tongs, aren’t they?” She inclined her head towards the wall, where the hard angry voices of Lady Cartwright and Peterwere still audible. “Told you it always happens when he turns up.”

I held out the chemise. “I brought this up for you, you dropped it in the kitchen.”

“Oh, thank you, Joanie. I mustn’t lose that one, it’s French silk.” She took it from me and placed it neatly in the top drawer. I sat down on Dorothy’s bed. Her room was so lovely: white and feminine and stuffed full of beautiful furniture and paintings and clothes. I got up and went to the wardrobe to gaze hungrily at her lovely dresses.

There was the emphatic slam of the bedroom door in the room next to us and then the sound of footsteps stamping away. Verity and I looked at one another and I bit down on the smile that wanted to show.

Dorothy’s own door opened and I leapt away from the wardrobe, expecting it to be Lady Cartwright. But it was Dorothy herself, wrapped in a white satin dressing gown with large embroidered poppies on the lapels.

“Oh, hullo, Joan,” she said amiably. I’ll say that for Dorothy, there wasn’t any side to her. She always greeted the servants by their preferred name and even though normally she would be expected to call Verity by her surname, she never did. “A hunter is what I ride, not what I call my maid,” I’d overheard her say, once.

If she was hungover, you would never have known. As usual, she was plastered in make-up and her hair hung in two precise curtains of smooth golden silk on either side of her face. Dorothy’s looks reminded me a little of an illustration I’d seen once in an old story book of Snow White, that of the wicked queen. Beautiful but a little bit frightening too. But then, appearances could be deceptive. Dorothy was mostly kind, if a little bit careless, and, like I said before, never made you feel the vast gap that yawned between ‘them’ and ‘us’.

“God, my head,” she groaned, flinging herself down on the bed and reaching for her onyx and silver cigarette case. “I’m going to have to tell Dickie not to let me near the champagne cocktails again. I can’t be trusted.” She lit her cigarette and tossed the lighter onto her bedside table. “Was that my brother doing all the shouting just now?”

“Afraid so,” said Verity. “He and your mother were having a bit of a row about money.”

Dorothy laughed cynically. “So what’s new? He’s such a bore. You know, he has a perfectly adequate allowance?” Of course, we didn’t know this, or I didn’t, though I didn’t confess my ignorance. Dorothy went on. “I mean, if I can’t get through it in a month, I can’t believe Peter can. What’s he spending it on? I simply can’t imagine.”

I couldn’t imagine it either. Imagine having that much money that you couldn’t spend it all in a month, despite all the cocktails, cigarettes, new dresses, handbags and trips to the theatre that you paid for. For a moment, I had to struggle not to let my envy show on my face.

I had to get back to the kitchen, anyway, so I murmured to Verity that I would see her later, bobbed a little curtsey to Dorothy and hurried back down the stairs.

The full family contingent sat down to dinner that night. One of the parlourmaids, Nora, was ill and in bed with a bad stomach, so it fell to me to wait the table. Not something I enjoyed – I was always sure I was going to spill something hot onto someone, or let the potatoes bounce off the serving platter and all over the floor. I remembered Verity telling me once about how she’d seen one of the parlourmaids in her previous place spill a load of hot peas down the cleavage of one of the guests, and then have the excruciating task of trying to help the screaming guest retrieve them. It had made me laugh a lot at the time, but now I cursed the memory and prayed that my hands wouldn’t shake and do anything like that.

As it turned out, it was fine. I handed the last dish of vegetables around and then stepped back to my place in the corner of the room, next to Mister Fenwick, the butler. It was quite dark in the room. The ground floor and first floor of the house were wired for electricity and there were adequate wall lights in the dining room, but Lady Eveline always demanded candlelight for the dinner table. “Wonderfully flattering for the complexion, candlelight,” Dorothy had said once and that was probably why her Ladyship insisted on that particular form of light. I felt pleasantly invisible over in my dim corner. If it wasn’t for the ache in my feet, I would have felt quite content.

I watched Lord Cartwright as he ate. He always cut his meat as if attacking it, with short jabs of his knife and fork, and swilled it down with wine. If he hadn’t been quite so wealthy and titled, I had the suspicion that at least some of the guests who’d eaten here on occasion might have thought him just a little bit uncouth. He wasn’t an attractive man – with his drooping moustache and ruddy complexion, he reminded me of nothing so much as a sunburnt walrus.

I found the trick to observing someone was to watch them for just long enough, but no longer. Stare intently at someone for too long, and, sooner or later, they look up and catch your eye. Try it, I assure you it’s true. So I watched Lord Cartwright for just long enough and then swapped my gaze to his wife. True to her class, she was barely touching her food, pushing it disinterestedly around the plate. I knew full well that she’d have a tray sent up later – I imagined that she’d absolutely gorge herself then, eating with both hands, with no dining etiquette to stop her. The sight of Lady Cartwright rejecting my lovingly made food began to anger me so I looked further down the table to where Peter Drew was eating, in a sort of stiff, unhappy way. He didn’t look like a man who was enjoying himself. Dorothy was seated next to him but she wasn’t eating either, just resting her sleek head on one hand, a cigarette held unlit in her long fingers. I couldn’t imagine either Lord or Lady Cartwright allowing her to actually smoke at the table. In that, I agreed with them.

Duncan Cartwright and Rosalind Makepeace were seated next to one another but weren’t talking. It may have been my fancy, but they seemed to be slightly turned away from one another, as if they were holding the side of their bodies closest to the other stiff. It made me remember that time I’d had to sit at the servants’ table at the position I’d had before Asharton – I’d had to sit next to the valet, who was a horrible man, and every dinner time it was the same; I hadn’t been able to let the side next to him relax at all.

I’d noticed that before, the slight tension that always seemed to be between Rosalind and Duncan. I made a mental note to ask Verity why she thought that was and then pulled myself together with a jump as I realised they’d finished their main course, and I was now expected to help the footmen clear the table.

After dinner came the inevitable washing up and the preparation of breakfast for tomorrow. At least Maggie, the scullery maid, was the one who had to do most of the scrubbing. Mrs Watling and I sat at the table to go through the supplies and plans for what we had to do tomorrow.

Verity came in after a few minutes, yawning. “Can I make up a milky drink, Mrs Watling?”

“Of course, love. Is it for Dorothy?”

Verity nodded, sitting down at the table. “She’s having an early night tonight, thank the Lord. I’m just about ready to drop.”

“Miss Dorothy won’t be wanting anything else to eat?”

Verity shook her head. “No, I wouldn’t have thought so.”

As she spoke, we could see one of the bells start jangling. “That’ll be Madam,” said Mrs Watling with a sigh. “She’ll be wanting her tray.”

“I’ll take it up,” I offered. I could see Lady Cartwright was in the library by the name on the bouncing bell, and I never missed an opportunity to visit the library. I love books. I love reading and writing, even if I barely get the chance to do either. The library at Merisham Lodge was large and square and filled with literally hundreds of books. I might even have a chance to sneak myself a new novel to read if I was sly about it.

“Good girl. Well, Joan, once you’ve taken that tray up you can turn in for the night.There’s nothing more to do here.”

Verity made the hot milk drink, yawning all the while, and carried it out the door, flapping a vague hand at me in goodbye. I went through to the pantry where the tray for Lady Cartwright was neatly laid out, covered in a white cloth, and picked it up with a grunt. At least the library was on the ground floor of the lodge, only one flight of stairs to climb.

There was no answer to my careful knock at the library door. I hesitated, knocked again and when there was silence, opened the door, picked up the tray from where I’d put it down on the floor, and edged inside.

I thought for a moment that the room was empty, but a second glance showed me Lady Cartwright over by the window, staring out at the dark garden. I could see her face reflected in the glass of the window and she looked deep in thought, almost, one might say, worried. Fearful, even? But of what?

“Your tray, Madam,” I murmured.

She seemed to come back to life then and turned. “Oh, yes,” she said, disinterestedly. “Put it there.”

I placed the tray on the table she’d indicated and straightened up. I knew a ‘thank you’ would not be forthcoming. “Will that be all, Madam?”

She didn’t bother to answer. She’d turned back to stare out of the window again, almost as though I wasn’t there at all. I thought about asking her whether she wanted me to draw the curtains, but decided against it. Instead, I bobbed a curtesy and saw myself out, thoughts of stealing a book forgotten.

Verity was fast asleep by the time I got back to our room. I sighed, a bit disappointed that we wouldn’t be able to chat. Instead, I fetched some clean water for the wash bowl on the stand, washed my face, cleaned my teeth and began the slow, laborious work of unpinning my hair. Verity had left the oil lamp burning, which she always did if I was going to be later than her. I could feel my eyelids drooping and knew I should just curl up under the blankets and let myself sleep, but part of me was cross that this was the only time I ever really got to myself and almost all of it was spent unconscious. I picked up my notebook and pen and started to write, continuing a story idea that I’d had while clearing up the kitchen that evening. I nurtured dreams of being a real writer, of seeing my own words in print.That was one thing I’d never confessed to anybody, not even Verity. That was the one dream I couldn’t bear to have stamped on or laughed at. Not that Verity would do either of those things, but still… It was no use, that night. I couldn’t keep my eyelids from fluttering closed. Giving in, I tucked the notebook and pen under my bed and turned off the lamp.