Chapter One

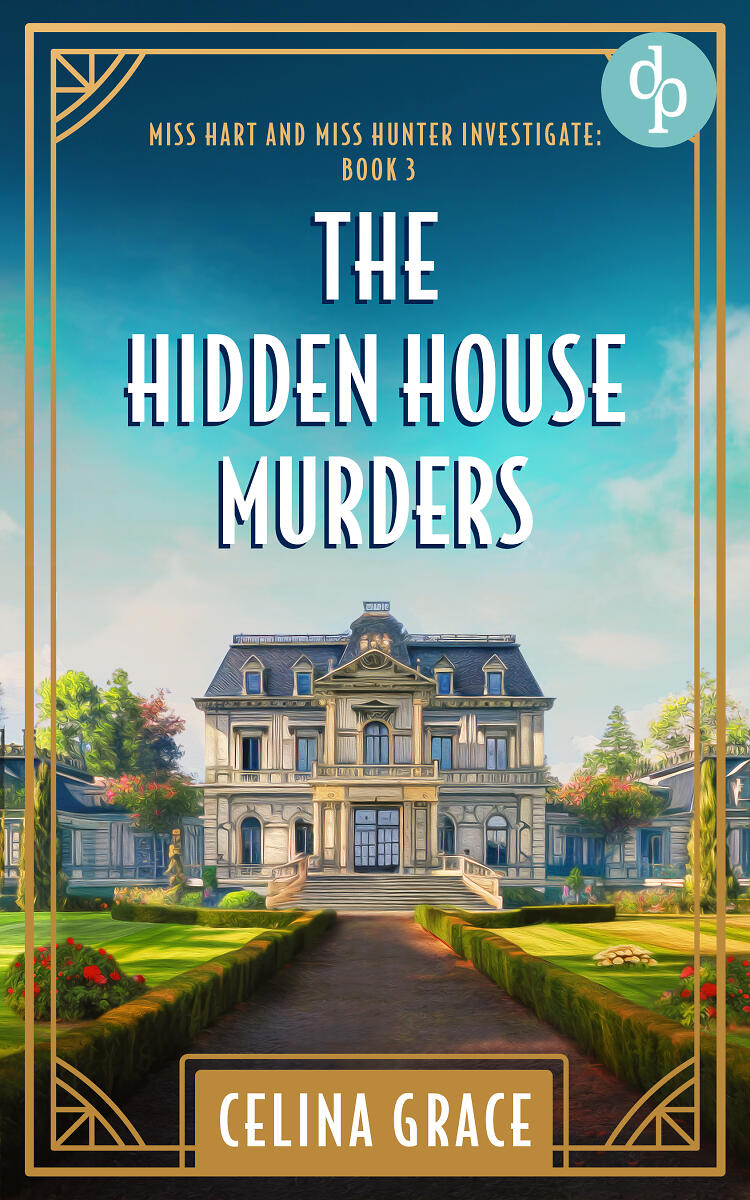

I didn’t think much of the house at first sight. It was big enough, I grant you; a large, red-brick stately pile surrounded on three sides by dense forest. As we drove up the winding driveway through the clustered trees, my first thought was that it was too similar to how Asharton Manor had been. Andrew parked the car in front of the front door. This house was nothing like as big as the enormous mountain of stone and glass that made Asharton, mind you. Hidden House was merely a big family home. It would be our home, mine and Verity’s, for the foreseeable future. I wondered how I was going to like it, living right back in the depths of the countryside again. Hidden House. It was an apt name. You would never know it was here, from the main road.

Verity got out first and I scrambled after her, trying to keep my knees together in a ladylike way. I looked up at the outside of the house. A rose bush grew up the side of the front door, although now, in late March, there were no flowers to be seen.

I was growing nervous now, as I always did when arriving at a new place. Verity and I had travelled down from London, firstly by train from Paddington to Winter Hissop, the nearest tiny train station. Andrew, the chauffeur cum footman of our London establishment, had met us at the station, which was a relief. I hadn’t been sure how we were going to travel the last five miles and hadn’t fancied walking, carrying all my goods and chattels. Not that there was very many of those.

“When does Dorothy arrive?” I asked Verity, somehow finding myself whispering.

She sounded distracted as she answered me. Her face was tipped up and I could only see the curve of her cheekbone beyond the edge of her purple cloche hat. “I’m not sure. Later this afternoon, perhaps, or tomorrow…” She trailed off and began to walk towards the front door.

“Verity!” I said, shocked. “Not the front door.”

She gave me an amused glance. “It’s fine, Joan. No servants’ entrance here. Just the front and back, and I know Mrs Ashford won’t mind us using the front.” Before I could stop her, she ran lightly up the three brick steps and rang the doorbell.

A woman who answered – which surprised me. I was used to butlers. But, I reminded myself, Mrs Ashford kept a small staff. Verity had informed me of that on the train journey down. All women, Verity had added with an expressive grimace that made me smile to recall it.

“Ah, Verity,” said the lady who’d answered the door. She was obviously the housekeeper. You could tell, not only from the bunch of keys that hung from her belt but from the air of calm authority that she exuded. She was quite a short woman but seemed taller, given the ram-rod straightness of her spine and the set of her shoulders. “And this must be Joan Hart.” I stepped forward and bobbed a curtsey. She gave me a quick once-over and nodded once, I hoped, in approval. “I am Mrs Weston, the housekeeper here. Joan, you will report to me directly. Verity, you will do the same, but I know that you know that already. Now, girls, are these all your belongings?” We indicated that they were. “Very well. Andrew, please convey these to the girls’ rooms on the second floor.”

Andrew began untying boxes and carpet bags from where they were strapped to the back of the car. Dorothy had insisted on her chauffeur accompanying her on this visit, as well as her lady’s maid. Apparently, Mrs Ashford didn’t drive and didn’t own a car. I wondered what the all-female staff would make of Andrew. He was quite young and quite handsome and could probably have his pick. It made me giggle a little inside to think of the flurry his arrival could provoke. I wondered about the women working here. Would they be old, young, middle-aged? Sober or gay? Suddenly, I missed our house back in London and the tightknit group of servants who worked there. Ponderous old Mr Fenwick, the butler, and Mrs Anstells, the housekeeper. The two maids, Nancy and Margaret, and the little tweeny, Doris, who helped me and Mrs Watling, the cook, in the kitchen. I wondered what they were doing in our absence.

I’d managed to gain a place here by the skin of my teeth. I’d been all set to say goodbye to Verity and retain my place at Dorothy’s London residence – she wanted to keep her staff on even while she was ‘recuperating’ in the countryside – but as luck would have had it, the cook at Hidden House had fallen ill and was sent away for her own recovery. She would be away for some weeks, and so Verity and Dorothy had between them persuaded Mrs Ashford to take me on as a temporary cook. I knew Verity had quite a lot of influence with her mistress, but I also prided myself on the fact that Dorothy truly did enjoy my cooking. I was looking forward to running a whole kitchen by myself; no longer a skivvy or even an undercook, but the one actually running the show. I was also slightly nervous. Although I knew my way about the stove and larder by now, this was a new household. I hoped fervently they wouldn’t go in for very exotic fare or something faddy, like not eating meat. I’d known a girl who worked in a kitchen for a gentleman who never touched meat. Not even beef steak or something like that. Very odd.

Shaking off my thoughts, I followed Verity and Mrs Weston into the house. From the start, I thought the house had a dull sort of feel to it. I’m sensitive to atmosphere in places. It wasn’t a bad feeling, more a sort of…fog about the place. A greyness. There wasn’t the feel of this having been a happy family home. It was nicely appointed, if a little bit shabby and worn. Old money – you could tell – but had it been old money that was now running out?

“Follow me, girls,” Mrs Weston said, leading the way up the stairs. They were wide, handsome stairs, carpeted in a dull red with brass stair rods and a long sweep of gently curving wood on which to rest your hand as you walked upwards.

Our room was on the top floor, of course; I hadn’t expected anything different. At least here, just as at Dorothy’s London house, there was only one staircase – not a separate one for servants. That always annoyed me. As we trailed upstairs, behind Mrs Weston’s straight back, I caught glimpses of other rooms as we passed them. A wood-panelled room on the ground floor that looked like a study or a library. A large bedroom with a four-poster bed topped with a cream silk counterpane. I wondered if that was going to be Dorothy’s room.

“What relation is Mrs Ashford to Dorothy again?” I asked, whispering so that Mrs Weston wouldn’t hear me.

“A very, very distant cousin, I think. More of an old family friend.” Verity’s cheeks were pink from the climb, clashing with her red hair. “She’s very elderly, something of an invalid – she doesn’t leave the house much. I think she’ll be glad of the company.”

“Does she know why… why Dorothy wants – needs – to come and stay?” I murmured.

Verity twisted up her mouth. “I’m not sure. As far as I’m aware, she thinks that Dorothy’s nerves need a rest and a few months in the country would help.”

“Hmm.” I wondered whether fudging around the issue would actually help Dorothy. Both Verity and I knew that Dorothy, whilst probably in need of a rest for her nerves, needed more help in battling her over-fondness for alcohol.

But it wasn’t exactly my worry. I meant to help Verity and Dorothy as much as I could, but I was probably better off in making sure that the meals were delicious and timely. The stairs got narrower and steeper as we left the first-floor landing. Here, I would imagine most of the family would have their bedrooms, with the second floor the servants’ domain. Still, as places go, it wasn’t the worst house I’d been in – not by a long shot.

There was a funny, round window on the second-floor landing, rather like the porthole of a ship. Gentle spring sunshine poured through it, making a dappled circle of light on the wooden floorboards. No carpet up here, just a few rag rugs scattered here and there. Mrs Weston opened the first door off the corridor and gestured for Verity and I to walk in.

It was quite a pleasant room, though not overly furnished and quite austere in decoration. There was an oval braided rug in the middle of the floor, a small dressing table and an equally small wardrobe. The thing I noticed immediately was that there was only one bed. Surely Verity and I wouldn’t be expected to share a bed? That little mystery was immediately solved by Mrs Weston’s next remark.

“Joan, this is your room and Verity has the one next door.” Verity and I exchanged glances behind her back; half gleeful, half apprehensive. It was quite exciting to think about having a whole room of one’s own – but might it not be a little lonely too? Verity and I had shared a room for years; it would be strange not having her there to talk to late at night or early in the morning.

Andrew had already delivered my two small cases to the room and had put them on the bed. It was the usual iron-bedstead type, although the counterpane looked quite new and the pillows relatively plump. I remembered one place I’d had where the bedspread had been an old curtain, just the brass rings removed from the top hem. What an old skinflint that master had been. And the mistress had been just as bad. I remembered the cook had had the eggs counted out for her every morning by the lady of the house. Actually counted out! I could imagine Mrs Watling giving in her notice if Dorothy ever did that to her, not that she ever would. Dorothy may have had her faults but meanness was definitely not one of them.

Verity and Mrs Weston had already left the room – my room, how strange it sounded in my head to say that –and I could hear the low murmur of their voices in the room next door. I began to unpack, unfolding and hanging my clothes in the wardrobe where someone had thoughtfully placed some hangers. I put my good pair of shoes on the wardrobe floor. There was only one more thing in my suitcase and I lifted it out carefully.

A bundle of paper, bound in string. I read the words typed on the first page; Death at the Manor and then the three words written underneath. By Joan Hart. I thought of all the snatched minutes and hours it had taken me to write it, pecking away at the ancient typewriter I had found in a cupboard at Dorothy’s London house. Of course, I had checked with her that it would be fine for me to use it. Dorothy being Dorothy had waved a hand airily and told me to throw it out of the window if I wanted to, that old thing. “Type away, Joan,” she’d said, “someone in the house may as well make use of it,” and she’d lit another cigarette.I held my precious play in my hands and then tucked it back into the suitcase, which I heaved onto the top of the wardrobe.

Pushing thoughts of my play away, I sat down on the edge of the bed to survey my new domain. Wonder of wonders, I had an electric bedside light, with a silk shade, and a small vanity mirror. Even a tiny shelf by the bed for books and ornaments. Feeling content, I got up, unpinned my hat and put it on the shelf. A rose-patterned china jug and washbowl sat on the dressing table but there was no water within it, so I went in search of the bathroom in order to wash my hands. I was glad to see there was a fireplace there – believe me, bathing in an unheated bathroom is not one of life’s most comfortable experiences. I suppose, in one way we were fortunate to have a bathroom to ourselves at all, especially in a smaller house.

Verity, myself and Mrs Weston all met in the corridor outside, and Mrs Weston gestured for us to follow her. “I’ve already arranged for a cold supper for this evening, Joan,” she said over her shoulder as she bustled away towards the stairs. “I suggest you make yourself acquainted with the kitchen and introduce yourself to Ethel, who’s the maid of all work here. She’ll be able to help you get settled.”

That was the first, slightly wrong note. I kept my face neutral and nodded, but I was conscious of a flash of annoyance. I wouldn’t even have my own kitchen maid? Verity, who naturally hadn’t thought anything of Mrs Weston’s remark, given her own position, hummed a little tune under her breath. I tried to be philosophical. This was a small household with an invalid mistress – it wasn’t likely that there would be heaps of grand dinners or evening soirées to cater for.

The three of us trooped back down the stairs, our heels clattering noisily on the bare floorboards of the first flight of stairs, the sound hushing once we reached the carpeted treads of the main staircase. As we passed through the downstairs hallway, a querulous but aristocratic voice was raised from behind the panels of one of the doors.

“Arabella? Is that you?”

Verity and I glanced at one another. Mrs Weston paused as if hesitating, and then moved towards the door behind which the voice had spoken. “It’s I, Mrs Ashford,” she said, turning the brass handle. “I’m just showing the new maids to their quarters.”

The cracked old voice spoke again, quite imperiously. “Why, then, you must bring them in to meet me.”

Verity and I exchanged glances that were somewhat alarmed. It was unusual to be formally introduced to the people you were engaged to work for. One may have encountered them at the interview for the position, but not always, and certainly not in the larger establishments. This would be a first.

Mrs Weston didn’t seem fazed by the order. “Come with me, girls,” she said, gesturing for us to go forward into what turned out to be the drawing room.

Again, it was comfortably if not luxuriously furnished.The carpet and furniture was a little worn although well maintained. A good fire burned in the grate at the end of the room and beside the blaze, in a green velvet armchair, sat the mistress of the house, Mrs Ashcroft herself.

She was a diminutive figure, more wizened and much older than I had anticipated. It was only as one got closer that one became aware of the undimmed gleam in her grey eyes and the firm set of her jaw, which spoke of someone used to getting her own way.

“And who might you be?” she demanded, as Verity and I got closer. Her left hand rested on the ebony head of a cane, the knuckles of her fingers swollen and bluish against the wrinkled skin of her hand. She wore an old fashioned ruby engagement ring, a cluster of blood-red stones that caught the light of the fire in an answering gleam.

Verity dropped a flawless curtsey. “I’m Verity Hunter, Miss Drew’s lady’s maid,” she said, in the proper, hushed, respectful tone.

“I see. And you, miss?” asked the formidable old lady, turning to me.

I swallowed, less confident than Verity. “I’m – I’m Joan Hart, the new – the new cook, milady.”

“Humph. I don’t have a title . Madam or Mrs Ashford will do for me.” I blinked and nodded. “Mrs Weston will assist you should you need anything or need to know of anything. You’ll find we run a tight ship here, but we all pitch in.” She favoured us with another penetrating gaze from those gleaming grey eyes and then nodded, dismissing us.

Mrs Weston led us out of the room and down the back staircase at the back of the hallway that led to the basement kitchen. I was dying to talk to Verity alone, to find out what she thought about all this, but it didn’t look as though I was going to get the chance. Mrs Weston ushered me into the kitchen and, after exhorting me to ‘get myself settled in’, whisked Verity away in the direction of Dorothy’s rooms. All we had time for was a wink from Verity as she went out the door and a grimace from me, hastily dropped from my face as Mrs Weston looked back.

The door to the staircase swung back into its frame as the two of them left. I stood in the middle of the kitchen floor for a moment, silently assessing my new domain.

Chapter Two

My first impressions were favourable. Although the kitchen was technically below ground, at least on one side, there was a row of windows set high into the back wall that brought the spring sunshine in. The back door was half wood, half glass panes, which brought yet more light to the room. The walls were whitewashed and the floor, thankfully, was of good red ceramic tiles, so much easier to keep clean than the pitted and rough flagstones that I’d had endure earlier on in my life. Quickly, I checked on the equipment. There was a gas stove as well as the range, which was good, but no refrigerator. A door to the side of the kitchen led me to the pantry with its marble-topped shelves. There was a large ice-box and barrels of flour, sugar and tea stood on the floor.

I wondered whether Mrs Ashford herself would meet with me to discuss the daily menus or if she would delegate that to Mrs Weston. It was not a question I would normally have asked, but this was a slightly different household to the ones I’d been used to. I moved around the kitchen, opening drawers, peering into cupboards and trying to acquaint myself with every inch of my new workspace.

I had just located the drawer where the aprons were kept, and was tying one about my waist, when there was a flicker of movement outside the glass of the back door. A moment later, it opened and a woman came into the kitchen.

“Oh,” she exclaimed in surprise when she saw me. Quickly, I curtseyed, believing (rightly, as it turned out) that she was Miss Arabella Ashford, the daughter of Mrs Ashford. Verity had told me about her on the journey down. She’s adopted, Miss Arabella. Mrs Ashford and her husband were never blessed with children of their own, but they took on Miss Arabella when she was about seven, I think. She was the daughter of one of Mrs Ashford’s friends who was widowed in the war and then died…

“You must be the new cook,” said Arabella, hesitantly. She seemed rather a colourless person: very fair with a washed-out complexion and somewhat prominent pale blue eyes. She was simply – even drably – dressed in a tweed skirt and a limp cream-coloured blouse. She had a sweet smile, though, which I saw a moment later and it brightened her face to something almost pretty.

“Yes, that’s right, miss. I’m Joan Hart. I arrived today.”

“Um. Jolly good.” I got the impression she wanted to walk past me but was unsure of doing so, for some reason. “I must go to my mother—”

“Very good, miss.” I bobbed a curtsey again and moved backwards so she could pass me. She gave me another quick and nervous smile as she walked away.

I waited until the door shut and turned back to my tasks. So, that was Arabella Ashford. Thankfully, she didn’t seem like the sort of overbearing, interfering type I’d sometimes run up against. There was another member of the household who Verity had also told me about, Mrs Ashford’s half-sister. Constance Bartleby was a widow and, from what Verity had told me, something of a poor relation. Apparently, she lived with Mrs Ashford as a sort of companion. Idly musing on what she might be like, I decided to go back upstairs to get my book.

Every cook of any note had her own book. It was a collection of recipes, short-cuts, tricks and tips of the catering trade and it was as precious as a Bible. As I climbed the stairs, still a little hesitant about using them, I thought about my play – the collection of papers far more precious to me. I still cherished dreams of being a writer, a playwright even, although nobody but Verity knew. I’d never shown her what I’d written. Perhaps I never would. Perhaps I’d never show anybody. Who was I, anyway, thinking I could write a real play? Even a real book, one day? At that very moment, it seemed the height of silliness. I was just a servant, a cook; that was all.

I found my book, my cookbook and trudged back downstairs, feeling melancholy. I met Mrs Weston coming up the stairs just as I was coming down. Although I knew I had a perfect right to be there, I still felt a little nervous. Mrs Weston was far more forbidding than our usual housekeeper, Mrs Anstells, although perhaps she would warm to me as she got to know me.

“Joan? Are you looking for something?”

“I was just fetching my book,” I said hastily, holding it out for inspection. Mrs Weston nodded.

“As I said before, I’ve arranged for a cold supper tonight. The only family members here tonight are Mrs Ashford and Miss Arabella. But I’m expecting you to prepare the breakfasts tomorrow, and from then on, the kitchen is under your control.” She looked at me severely for a moment, as if she wondered whether I’d be up to the task. “You seem quite young to be a fully qualified cook, Joan.”

“I’m twenty,” I said, unsure whether that would make things better or worse. “But I’ve plenty of experience.”

Mrs Weston’s mouth twisted for a moment, as if weighing up the truth of that statement. “Well, Miss Drew spoke highly of you and we could certainly do with the help whilst Aggie is indisposed.”

“I’m sure I’ll try and do the best I can.” We faced each other in the middle of the staircase.

“No doubt.” She looked at me searchingly again for a moment. “Have we met before? Your face looks somewhat familiar…”

I cursed inside my head. She was remembering those newspaper photographs, when the case of the Connault Theatre murders had come to court. Both Verity and I had had to testify and, being young and (in Verity’s case) comely, the newspaper interest had been huge. Thankfully, as it had with the Asharton Manor case, the tumult and publicity had quickly died down.

“I don’t believe so,” I said, with as winning a smile as I could. “Could I just ask you about the tradespeople? Where do I find their contact details?”

“Let me show you.” Mrs Weston led me down the stairs and thankfully, her moment of recognition seemed to have passed.

The afternoon passed in a blur of stock-taking, making orders for the morrow, rearranging the kitchen to my satisfaction and introducing myself to Ethel, the maid of all work. She was a plump young thing of sixteen, rather adenoidal, but she seemed a nice enough girl and a willing worker. That was good, because despite it being a small household in terms of the family, there were still five servants, including myself, to cook for.

It was a pleasant kitchen in which to work. The glass-panelled back door looked out onto the gravel drive that ran along the back of the house. At about four o’clock that afternoon, I saw Andrew drive the car past to park it over by the far garden wall. He’d obviously gone to collect Dorothy from the train station. I wondered, somewhat uncharitably, if she’d got drunk on the train. I’d have to wait until I spoke to Verity later to find out.

It was a tiring day, as new days in new positions are. So many things to remember; rooms and passageways and where the lavatory was located. New names and new faces. Just the smallest things took up one’s mind: where the salt cellar was kept, how the tea towels were folded, what kind of china was required for afternoon tea. It wasn’t as if I could slope off to bed early either, cold supper or no cold supper. I stayed up late, making sure everything was ready for breakfast the next day. Ethel had the job of getting the range alight and the kettle boiling, and before I said goodnight to her, I reminded her of that. She nodded nervously – she was a bit of a frightened rabbit. Mind you, I remembered my first days in service. I was a-tremble from dawn until dusk, terrified of getting something wrong. I smiled reassuringly at Ethel and dismissed her.

I was climbing the stairs to my room when the second wrong note occurred. I passed the first floor, where the family bedrooms were located. I could hear the querulous but surprisingly strong voice of Mrs Ashford coming from one of the bedrooms, the second one along the corridor.

“There’s no use getting in a pet about it. You can weep and moan all you like, Arabella, but that’s an end to it.”

Shamefully, I allowed my footsteps to slow. I could hear a female voice answering Mrs Ashford, but it was too low and tear-soaked for me to hear exactly what it was saying.

“There’s no need to make a fool of yourself. Why in heaven’s name you would think that someone like him would be interested in someone like you, I have no idea— “A soft wail undercut this remark. “Oh, my dear, don’t take on so. There are plenty of other young men out there who are much more suited to someone of your – your temperament.”

The other voice spoke up and this time I could hear that it was Miss Arabella. “You can’t tell me how to live my life—”

“No, I can’t, but I’m telling you now, Arabella, you’re a fool if you think he cares two buttons about you. And even if he did, he’s not the kind of husband that I’d like for you. He may be wealthy but his father’s as vulgar as they come.”

“You’re such a snob.” I could hear the anger in Arabella’s voice even through the closed door. “You should hear what you’re saying. You can’t control people like – like puppets, getting them to dance to your every whim, just because—”

I could hear Mrs Ashford’s cracked, wheezing laughter. It had a cruel sound to it that made me shiver; less a sound of mirth and more of pleasure in someone else’s pain. “Oh, I can, my dear. I’ve been doing it all my life.”

Silence emanated from the room. I held my breath. I knew I should keep walking, that it was none of my business, but I was transfixed by the drama going on unseen behind the wooden panels before me.

After a moment, Mrs Ashford spoke up again and her voice was once more normal, no-nonsense and brisk. The nasty undercurrent I thought I had just heard was gone. “Now, let’s not argue with one another. You’ll soon see I’m right. I just wish you could understand it before you get yourself hurt.”

“You’re wrong.” I could tell Arabella was starting to cry again.

“Now, come along. You and I both know there’s always been one way of changing your mind, so please don’t force my hand and make me take that route.”

A watery gasp from Arabella. “What – what do you mean?”

“You know what I mean, Arabella.”

Another silence. Unable to help myself, I pressed my ear to the door.

Then Arabella spoke again, in a dull monotone. “I hate you.”

“Oh dear.” Mrs Ashford sounded entirely normal, not upset in the slightest. “Yes, that always was your response when you realised I was right all along.” I could hear her wheezing sigh. It was funny, but listening to her from here, without seeing her, you could almost forget she was old. Her tone changed to something much kindlier, almost wheedling. “Now, now, don’t go upsetting yourself. There’s no reason why you can’t meet someone much more suitable. Someone you might even know already. It’s not as if you won’t have money – that is, if you’re willing to—”

A door opened below me in the corridor, and I jumped like a scalded cat, snatching my ear from the door. Heartbeat thumping in my ears, I turned and began to climb the stairs again, trying to run away from the room without making any noise. I really must not be caught eavesdropping on my first day in the job. It was a terrible habit of mine, although I knew I was far from being the only servant to do so. One had such little power in life; it seemed only fair to balance it up a bit by being aware of what was going on around you.

I reached my room without incident, telling myself all the way that listening at doors was a little bit naughty but nothing so bad, though I had the uncomfortable feeling I was fibbing to myself. At least I didn’t snoop, I told myself. I didn’t read private letters or diaries, or poke around in drawers that didn’t belong to me. I’d only started listening because I’d overheard something. I kept trying to justify myself until I realised I had to look away from catching my own eyes in my little mirror. Think about something else, Joan, and shut up.

With an effort, I switched my thoughts. So, Miss Arabella was in love with an unsuitable man, was she? Well, she wouldn’t be the first, and she wouldn’t be the last. I sympathised but not too much. At least she had the time and the energy to actually meet someone. Fat chance of me ever having a sweetheart, stuck in front of an oven or a sink all day… For some reason, the face of Inspector Marks came into my mind, and I sighed. Ever since our meeting, during the Connault Theatre murder case, I’d hoped – what had I hoped? That he’d visit me? Court me, even? I blushed to hear myself. There was nothing doing, I told myself firmly. A man like that wouldn’t be interested in someone like you. I laughed. Those were almost exactly the words I’d heard Mrs Ashford speak to Arabella. Perhaps we weren’t so different after all.

I was wearily unbuttoning my dress when there was a knock at my bedroom door and a moment later, Verity’s flaming red head poked into the room.

“Joanie. Are you dead on your feet?”

“Very much so.” I sat down on the edge of the bed with a sigh echoed by the groan on the bedsprings. “I haven’t even done any cooking today and I’m exhausted.”

“Me too.” Verity came in. Tired she may have been but she still looked wonderfully smart in her silk blouse and wool skirt. Dorothy’s cast-offs, yes, but they were of such good quality that they still looked new. I sighed and yanked at the last button. Lady’s maids were expected to dress smartly, so I couldn’t exactly fault Verity for doing just that, but it always made me feel even more of a dishevelled mess than I already was.

“Joan, you’ll have that off. Let me.” I felt Verity’s gentle fingers free the reluctant button from its button hole.

“Thanks.” I peeled the dress off me and hung it up in the wardrobe – now there was a luxury, a wardrobe of my own. I’d been used to a peg rail before.

“Do you think you’ll manage? With the kitchen, I mean?”

“I hope so.” I thought, with a qualm, of the busy day ahead of me tomorrow. “Is there anything I should know about? Any visitors expected?”

“Ah, funny you mention that. There is.” I turned expectantly to Verity, who was primping in front of the dressing table mirror. Her gaze met mine through her reflection. “Mrs Ashford’s nephew’s expected tomorrow. Him and a Cambridge chum.”

“Oh yes?” I felt an extra spurt of anxiety. If the nephew was at Cambridge, then he was almost certainly a young man and, as I knew, young men had prodigious appetites. I hoped we had enough meat ordered from the butcher.

“He’s called Michael, Michael Harrison. I can’t remember what his friend’s name is.”

“So, how does he fit in here?”

Verity tucked the last wave of hair in neatly. “He’s the son of Mrs Ashford’s sister. Not Constance Bartleby, another one. Something like that. Bit of a rogue, apparently, according to Dorothy, but nice with it. She said Arabella’s awfully sweet on his friend, whatever his name is.” She chewed her lip for a moment, staring into the mirror. “Raymond! That’s it. Yes, Arabella’s very keen, apparently, but him not so much.”

That must have been the man that Mrs Ashford was taking Arabella to task about. “So, Arabella and Michael are cousins?” I asked.

“Well, sort of. Not blood related. Which is probably just as well, as apparently Michael had a bit of a soft spot for Arabella at one point, but she wasn’t interested.” I listened, trying to sort out all these romantic entanglements out in my hand. One thing about Dorothy, she always knew the latest gossip. Verity went on speaking. “No, she didn’t want anything to do with him, according to Dorothy. Goodness knows why, as apparently he’s really quite handsome.”

“Really?” I said, cheering up slightly. Yes, young men in the house may have meant extra work but if they were decorative, then at least you got something out of having to run around after them.

Verity giggled. “Well, you know Dorothy. She’s got an eye for a comely young man, hasn’t she?”

“How is Dorothy?” My curiosity about my mistress was enough to distract me from the worries about the visitors. Although, I supposed that here, Mrs Ashford was technically my employer.

Verity shrugged. “She seems fine, at the moment. She took a sleeping pill and went straight to bed.”

I pulled my shawl over my shoulders. “Had she—” I began and then shut my mouth. I wanted to ask if she’d been drinking on the journey down here but really, what business was it of mine? It was impertinent.

Verity looked at me enquiringly. “What, Joan?”

I shook my head. “It doesn’t matter. Listen, V, I’m all in. I’m going to get some sleep.”

“Rightio.” Verity came over and gave me a squeeze. “Do you think you’ll like it here, Joanie?”

I yawned. “Sorry. Yes, I think so.”

“You don’t think the work will be too much? You know, not having a kitchen maid as such—”

I felt a burst of gratitude. She had been listening when Mrs Weston had mentioned that fact after all.

“Ethel seems like a likely enough worker. I’m sure we’ll manage.”

Verity caught my yawn. When she’d stopped, she smiled and said, “Well, it’s hardly Asharton Manor, is it, Joanie?”

“Thank goodness.” Something occurred to me then. “We’re not that far from there, are we, V?”

“Not that far, no.” We caught each other’s eye, and I could see she was thinking the same thing as I was. “Try not to worry about it, Joan. It’s a long time ago now. Another lifetime, almost.”

“I suppose so.” I thought for a moment of the manor; its golden, treacherous surface, the darkness of the pine forest encircling it.I suppressed a shiver.

“Well, I’m off to bed.” Verity flapped a hand at me in a goodbye and sloped off, shutting the door behind her. “Don’t let the bed bugs bite.”

I continued to get ready for bed. I thought, as I always did, of sitting down and writing something. But, as always, I was too tired. Instead I climbed into the strange bed, clicked off my little bedside light and slid down under the blankets and into sleep.