Nancy

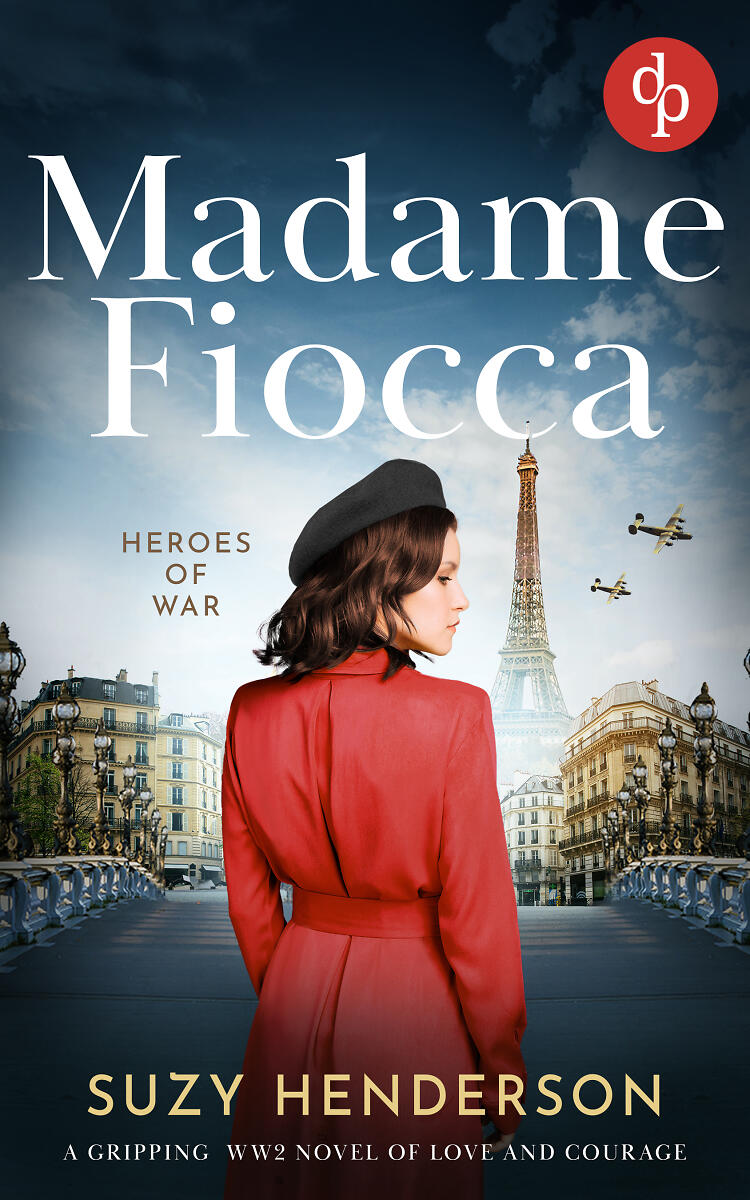

There were three things I dreamed of doing with my life: visiting New York, London, and Paris. New York came first, a city that embraced me with its electric pulse and towering ambition. I fell in love instantly. Then came London—at first, a grey and uncertain place, but as I wandered its historic streets, it slowly revealed its charm, and I found myself captivated by its depth. Paris, though, was different. When I arrived on a long weekend, the City of Light wrapped me in its magic. Paris was love at first sight. It didn’t take long before it became my home, the base from which I reported for the Hearst Newspaper Group. I, Nancy Wake—a New Zealander raised in Australia—now chronicling world events from the heart of France. It was an exhilarating new life, a sharp contrast to the one I’d left behind.

Paris in the 1930s was a city that sparkled with elegance and style. Women were effortlessly chic, draped in the latest fashions—flowing dresses, tailored gloves, and delicate hats. Their grace was unmatched, their style a step above the rest of the world. The city itself brimmed with romance: gallant men, champagne that bubbled like laughter, candlelit dinners, and streets filled with the scent of fresh flowers. It was a dreamscape for a girl like me, one where suitors would arrive at my door and ensure I was escorted home safely at the end of the night.

I was a flirt, drawn to handsome men and the thrill of attention. I was young, carefree, and more than a little dizzy with it all. But I never sought love—it found me, unexpectedly, in a time when the world was teetering on the edge. Hitler had risen to power in 1933, his Nazi ideology spreading like a dark stain across Europe. Political unrest simmered, and I could feel the tension in the air, a forewarning of the storm to come. The Spanish Civil War erupted, a bitter prelude to the greater conflict looming on the horizon. Others might not have seen it, but I did.

And then, in 1940, it happened. The German army marched into Paris, and the city fell silent beneath a blanket of swastika flags. France, once proud, was defeated, and the sight of it brought tears to the eyes of Parisians. But within that sorrow, a spark ignited—a flame of resistance that started small but grew stronger with each passing day. We answered General de Gaulle’s call, those of us who refused to bow to tyranny. This was the chance I had longed for, to fight against the evil that Hitler had unleashed. I played my part, and the French came to know me as ‘L’Australienne de Marseille,’ the girl who always laughed, even in the face of war.

People often ask me if I would do anything differently, given the chance. After much thought, I always answer the same way: ‘If I had my time again, I’d do it all over, despite everything.’ I live with the consequences, carry the weight of guilt and grief. The ghosts of my past linger in the quiet moments, their presence like a soft breeze, their voices whispering in the corners of my mind. Memories that will live on until I breathe my last.

Marseille

August 1944

The wolves have fled. The ground rumbles beneath my boots, tremors snaking up my legs, tingling along my spine. In the distance, the low growl of engines swells into the roar of a convoy—Allied trucks, a sound that would be sweet as birdsong on any other day, but not today. Marseille is free at last, yet my heart remains captive. How I longed to share this moment with you, Henri, my love. Our home, our perfect home. I bite my lower lip, blinking away tears.

Monsieur Dufort, our concierge, had looked so shocked when I arrived earlier. His usually composed demeanour shattered as he embraced me, his thread-veined cheeks wet with tears. I didn’t mind. We were all out of character today.

‘Madame Fiocca. I can hardly believe it’s you,’ he said, wiping his eyes. ‘We all thought you were dead!’

I forced a smile. ‘So many are dead or missing.’ What I truly wanted to say was that I’m dead inside. Instead, I gritted my teeth and murmured, ‘I’m so glad to see you.’

‘The Gestapo gave your apartment to female German officers,’ he explained, his hands rising helplessly. ‘There was nothing I could do.’

That explained the devastation inside. Broken ornaments, rubbish strewn across the floors, overturned furniture—our home, a shell of what it once was. They had taken almost everything, save for your armchair, lying on its side by the fireplace. As I dragged it upright, I pictured you sitting there, threading your fingers through your dark, wavy hair, tousling it in that familiar way as you unwound after a long day at the office. The scent of saffron drifted from Madame Dumont’s kitchen, mingling with the taste of your warm lips as you drew me close. But when I opened my eyes, there was only emptiness. A tightness gripped my chest, and I couldn’t think anymore.

I sit on a wooden crate in the cellar, gazing at the tattered green book on my lap—Anne of Green Gables, the last relic of my past. Nothing left but a couple of armchairs and this old childhood novel. The walls around me hold our memories, whispering echoes of the words we once spoke. Earlier, in the bedroom overlooking the devastated harbour, I was sure I heard you call my name: Nannie. I close my eyes and take a deep breath, but the tears won’t stop. The salty tang coats my lips, and the musty air presses in, stifling.

Den’s voice breaks my reverie. ‘Come on, Duckie. Let’s get you a nice cuppa.’

He means well, a tower of strength even as he grieves his own loss. I gulp down the lump in my throat and wipe my eyes on the sleeve of my khaki shirt. ‘I need a proper drink, Den.’

He crouches in front of me, his eyes full of concern as he listens. ‘They took everything. Trashed the rest.’ Everything of beauty, of worth—everything that represented the life we built together. All gone.

He rests a hand on my shoulder, offering what little comfort he can. ‘It could have been different. Why did I get involved?’ I say, my voice trembling. Henri indulged me, never said no. I squeeze my eyes shut, wishing it could chase away the demons, but I know better now. There’s no escaping this. I must face it, move on. Yet Henri’s voice lingers in my ear: Nannie, you are impossible. Of all the women I could have married, how did I choose you? I bite my lower lip, wishing he had never chosen me at all.

‘Don’t think like that, Nancy. You’ll go mad.’ Den pulls a packet of Players from his grease-stained shirt pocket, hangs a cigarette in my mouth, and strikes a match.

I inhale deeply, the nicotine surging into my lungs. The cigarette glows, a single jewel of light in the darkness.

‘You did what you had to do, what you thought was best. And you’ve done some bloody amazing things. If not for you, there’d be hundreds, maybe thousands more dead.’

His warm smile softens the edges of my despair, but I know he’s making light of it for my sake. Yes, we made a difference, but at what cost? I sigh, exhaling all my options into this decaying cellar, out of time, out of luck. My mother’s voice rings in my ears, her tongue sharp, a Bible clutched in her hand. You’ll come to no good, my girl. You’ll see.

‘She was right,’ I whisper. ‘She was right all along.’ I hunch over, tracing a fingertip along the worn cover of my book. The young girl with red hair stares back at me, defiant. Anne of Green Gables—a heroine who faced hardships, overcame them, and made her way in the world. ‘Her story ends well,’ I mumble.

‘What’s that, Duckie?’ Den asks, puzzled.

‘It doesn’t matter.’ I hadn’t understood Mum’s anger as a child, nor as an adult, but now I see it for what it was: pain. All those years of fighting, the bitterness cocooned in my chest. Perhaps she did love me. Perhaps she couldn’t help how she was. She was hurting, too. I bury my head in my hands, a cry escaping my lips as tears spill over. But then, I lift my head, straighten my back, and draw in a deep, steady breath.

Den pulls me to my feet. This old book is all I have left of my childhood, of my father’s stories, of home. The memories wrap around me like an old friend, and I’m thankful for their warmth. I run a hand through my matted hair, thick with road dust. It’s time to leave. I blow out a breath as a storm of thoughts swirls in my mind. My stomach churns, my legs tremble. How I long to stay, to believe that everything can be as it was. But Mum was right. ‘You silly girl,’ she used to say. I’ve been here before, on the brink of leaving, my luck running out.

I recall the words I muttered then, as I walked away with my head held high: Just one foot in front of the other, Nancy. One step at a time. Tears fill my eyes as I slip on my sunglasses and grit my teeth. We stride out into the harsh glare of the sun, the breeze like a furnace. The smell of fish lingers in the air like death, and nausea stirs in my gut.

As I turn back for one last glance at our window, I remember standing there, looking out over the harbour, drunk on love and life. A piece of me has died, a piece I can never bury. In my heart, Marseille will always be my home. Dear God, forgive me.

Chapter 1

February 1933

The RMS Aorangi II surged forward, its engines thrumming steadily beneath me, as I cast a wistful gaze at the receding shores of New York. The figure of the lady in verdigris, the Statue of Liberty, diminished on the horizon. Lost in reverie, I tried to imagine the emotions of those who had fled persecution, catching sight of her iconic silhouette for the first time from the frigid waters of the Atlantic, relief swelling in their hearts, worry lines softening into hopeful smiles. In their eyes, I could almost see a flutter of butterflies as they beheld the symbol of freedom, safety, and renewed hope, etched against the skyline.

I, too, had fled—though not from persecution, but from the confines of a life that had become unbearable. At sixteen, I left home. Life had turned upside down the day Dad left. I loved him, adored the bones of him. He always found time for me, scooping me up in his strong arms after a day’s work, spinning tales that made me giggle, singing ‘Waltzing Matilda’ as we danced around the room. Every morning, he’d go off to work, and every evening, I’d wait by the garden gate. Until one evening, he didn’t come home. As I swung on the gate, Mum hollered at me to come inside for the twentieth time, and Gladys, my older sister, marched outside, scowling as she dragged me indoors by the hand.

‘Dad’s gone to America,’ Mum muttered, something about him making a film of the Māoris. I didn’t understand back then.

‘When will he be back?’ I asked, but she’d already wandered off. I found her sitting at the kitchen table, the Bible open before her, a frown etched deep in her face.

‘He’ll be back home in a few months,’ she snapped, lowering her bulging eyes to the scriptures.

Her coldness stung, and I missed Dad’s warm embrace even more. At night, I’d lie awake, listening to the creak and groan of the staircase, hoping each sound might be him returning home. My elder brother Stanley said all houses squawked in the night as they cooled down, but to me, it felt like our home was mourning too.

We lived in a lovely spacious house in Sydney, having moved from our native New Zealand when I was two. With five older siblings, I often felt lost in the crowd, except when Stanley was around. He always made time for me, though his service in the navy meant he wasn’t home much. One day, I noticed that the gilt-framed picture of Mum and Dad on their wedding day had vanished from its place on the oak dresser. No one said a word, and Mum became even more distant, retreating deeper into her Bible. That was when I realised Dad was never coming home again. A wound opened inside me, a hollow that ached, and I cried myself to sleep night after night. Ever hopeful, I would swing on the garden gate in the evening, looking out down the street, waiting, hoping for a glimpse of him. Life carried on, the Galah birds screeched as they settled in the Jacaranda trees in the evening, and I never saw Dad again.

One day, while I played in the garden, Stanley called me over. ‘We have to move, Nancy,’ he said. ‘To a new house, not far from here.’

‘But I don’t want to leave this one,’ I protested. How would Dad find us if he came back?

‘It’ll be okay, I promise.’ Stanley hugged me tight, swiping the tears from my eyes. ‘Be a brave girl, Nance. Help me pack your things.’

But it wasn’t okay. Life with Mum became unbearable, so I ran away at sixteen, found work as a nurse in a mental asylum, and eventually returned to Sydney at eighteen. I managed to find a job and a place to live, scraping by while dreaming of seeing the world. Then, a letter from Aunt Hinemoa arrived out of the blue. ‘Thinking of you,’ she wrote, with a cheque enclosed for two hundred pounds—a lifeline. Mum never approved of her sister, who had run off with a whaling ship captain. Hinemoa was the black sheep of the family, much like me, I suppose. So, like her, I left Australia to sail around the world. Canada, New York, and England beckoned.

New York was everything I’d imagined and more, bustling with life, nightclubs, and a river of alcohol flowing despite Prohibition. I’d never drunk so much, yet rarely felt the effects. And snow! I’d never seen snow before—icy flakes landing on my lashes, the taste of cold on my lips, my toes frozen through my boots. Leaving was bittersweet, but England beckoned, and with it, a new life studying journalism in London.

Onboard the Aorangi, life was pure opulence, like a stately home at sea, with grand lounges, sumptuous chairs, furnishings and real open fires. It was heaven to be waited on, a far cry from the life I’d left behind. Australia had never felt like home. Maybe travel was in my blood. I was born in New Zealand, with Māori and Huguenot roots on Mum’s side, British on Dad’s. A blend of cultures and histories. Was it any wonder I never quite knew who I was?

* * *

We docked in Liverpool on a grey, foggy day; the weather matched the dreary mood that had settled over us as we sailed along the Mersey. Mist slipped overhead, mingling with chimney smoke, and draped itself over rows of drab buildings and homes, casting a sombre frown over the city. As we approached the dock, the fog lifted just enough to reveal a splendid building with a clock tower, and further along, a majestic statue of King Edward VII on horseback.

The port teemed with life. Carts stacked high with wooden crates rumbled by, while men hauled trolleys laden with sacks, their efforts straining ropes taut. The whinny of horses cut through the air, thick with the scent of manure, while the clickety-clack of trains echoed from the overhead railway.

A man hurried past with a little girl in tow, their hands clasped tightly as they dashed for a tram. The sight jolted my memory, and suddenly I was back in Sydney, swinging on the garden gate, waiting for a father who would never return. A tender lump formed in my throat, and I turned away. Mum had been so hard on me after Dad left. Later, I learned the bitter truth—Dad had sold the house out from under us, leaving us with nothing. Though I still adored him, that didn’t excuse his actions. He was a bastard.

The porter loaded my luggage onto the train as I settled into the first empty carriage I found. The platform buzzed with activity, and soon enough, people filed in behind me. An elderly couple took the seats opposite, followed by a tall, thin woman who darted in like a minnow, a little girl trailing behind her. Despite the bustling scene, I wasn’t afraid of journeying alone. Home had been a lonely place, and I’d been forging my own path for so long that solitude felt like an old friend. In it, I found peace and strength.

As the train lurched forward and the countryside blurred past the window, the steady rhythm of the wheels on the tracks seemed to lull the carriage into a calm. Before long, the little girl drifted off to sleep. When she cried out in her dreams, her mother instinctively reached out, brushing a kiss across her brow, and an ache gripped my chest.

Mum had never shown me such affection, her growing obsession with the Bible consuming her more each day. Her idea of comforting words came as recitals of biblical verses—usually condemning me in the process. She often told me I’d go to hell for this and that, and for a long time, I believed her. But as I grew older, I began to see that religion had become her refuge, a place to hide after her world collapsed. Life hadn’t been easy for any of us.

I turned my gaze to the window, watching the English countryside flash by, and willed myself to focus on the future. The past was a heavy burden, best left behind. Resting my head against the seat, I closed my eyes, seeking solace in the gentle rhythm of the journey.

When the train pulled into King’s Cross, I waited as the others disembarked, taking in the bustling station. London! Well-dressed ladies strutted across the platform, people jostled their way through the crowd, and a group of soldiers stood around a pile of kit bags, their uniforms crisp in military khaki.

Stepping off the train, I felt the city’s energy wash over me like a wave. I hailed a cab to the Strand Hotel, where I’d booked two nights, the thrill of London pulsing through me. Soon, I’d begin my studies at the School of Journalism—Nancy Wake, reporter-to-be. It felt right, a career with the promise of travel and adventure, with Paris shimmering on the horizon. And I was determined to see Paris.